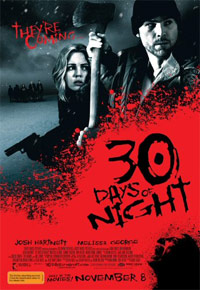

30 Days of Night (Dir. David Slade, 2007):

30 Days of Night (Dir. David Slade, 2007):

Sheriff Eben Oleson: Hell of a day.

The Stranger: Just you wait.

Successful horror movies dig into our unconscious and not-so-unconscious fears: abandonment, entrapment, dismemberment, loss of loved ones, all the bad stuff. Attach vampires to the above and you can add decapitation, eternal damnation, and engorged incisors to the list. So many vampire flicks and parodies have come down the path over the years that it would take a lot to overcome most folks’ built-up indifference to the genre. David Slade’s 30 Days of Night, based on the three-issue comic series by Steve Niles, attempts to do so with a few tricks in its arsenal. For one, it’s set in the northern Alaskan town of Barrow, a desolate place that is submerged in darkness for 30 days each year (for the record, in real life it’s 67) — the perfect feeding ground for bloodsuckers who don’t mind dining in sub-zero temps. The selection of Slade, best known for the gritty Heath Ledger drug drama Hard Candy, also hinted that the film wouldn’t be splatter hijinks as usual — not much difference between self-destructive addicts and undead junkies, after all.

The first image of the film, in which a Stranger (Ben Foster) emerges at the top of a peak, the beached wreckage of a freighter behind him, is a beaut. In the valley below, the residents of Barrow prepare to pack it in for the winter, as all communications and transport routes to the town will be cut off. Keeping a watchful eye on the residents is young sheriff Eben Oleson (Josh Hartnett) and his deputy Billy (Manu Bennett). Through them we meet the usual motley cast of characters that you know will come into play later in the film: Beau the crotchety misanthrope (Mark Boone, Jr.), a son nursing a father with Alzheimer’s (Craig Hall and Chic Littlewood), and most crucically, Eben’s estranged wife Stella (Melissa George) and his little brother Jake (Mark Rendall), the former getting stuck in town when she misses the last flight out. The tension builds in slight degrees as the sun sets on Barrow: cell phones are inexplicably found destroyed, sled dogs are mutilated, power outages take hold, and the mysterious deaths begin to rise. As the chill feeling of isolation grips the ever-dwindling nest of survivors, we rub our hands, ready for the sensual and emotional assault to reach the next level.

It never does. When we get our first glimpse of the vampires, led by Marlow (Danny Huston, who proves you can overact even when speaking in an unintelligible language), tearing into helpless victims with the relish of pigs in slop, you can’t help but suppress a titter. Slade does what he can to keep things anchored, and slips in some snarky humor; Mark Boone, Jr. gets most of the laughs as the don’t-give-a-damn survivalist — you wouldn’t want to have him over for dinner, but you sure want him around when you need to fight off hungry bloodsuckers. It isn’t enough, though, as the cliches of the genre come into play — plenty of graphic, CGI-assisted beheadings, survivors hiding out in attics and abandoned stores, internal dissension as our heroes try to decide what to do or where to go next, heartfelt connections between estranged lovers, noble sacrifices. Even the suspense of the time element (if only they can survive for 30 days…) goes nowhere, as we confusingly skip forward days and weeks at a time, with little explanation as to how our heroes got from point A to point B, or even how they survived with next to no food at point B for so long.

It never does. When we get our first glimpse of the vampires, led by Marlow (Danny Huston, who proves you can overact even when speaking in an unintelligible language), tearing into helpless victims with the relish of pigs in slop, you can’t help but suppress a titter. Slade does what he can to keep things anchored, and slips in some snarky humor; Mark Boone, Jr. gets most of the laughs as the don’t-give-a-damn survivalist — you wouldn’t want to have him over for dinner, but you sure want him around when you need to fight off hungry bloodsuckers. It isn’t enough, though, as the cliches of the genre come into play — plenty of graphic, CGI-assisted beheadings, survivors hiding out in attics and abandoned stores, internal dissension as our heroes try to decide what to do or where to go next, heartfelt connections between estranged lovers, noble sacrifices. Even the suspense of the time element (if only they can survive for 30 days…) goes nowhere, as we confusingly skip forward days and weeks at a time, with little explanation as to how our heroes got from point A to point B, or even how they survived with next to no food at point B for so long.

The lapses in narrative momentum might be more forgivable if the characters were memorable, but no such luck: Hartnett makes for a snivelly protagonist, and while George is easy on the eyes, her repartee with Hartnett doesn’t get much deeper than the usual “we couldn’t get along, but I guess we love each other after all” shtick. Foster puts in the most striking performance as the Stranger, although “performance” may not be the best way to put it: twitching like there’s no tomorrow, his face nearly coal-black with grime and an unkempt beard, eyes bulging, every word out of his mouth a weasel’s rasp, he is an instant parody, Charlie Prince from 3:10 to Yuma by way of Hammer Films.

True to the comic, 30 Days of Night comes to a bittersweet conclusion, adhering to its themes of macho sacrifice and love regained and lost. In other words, it comes down to a fistfight between Josh Hartnett and Danny Huston that ends with yet another variation of someone’s head getting disconnected from his trunk. “Next time they’ll take out Point Hope, Wainwright,” a character intones breathlessly at one point — not exactly the type of thought that sends shivers of dread down your usual moviewatcher’s spine. As a horror movie, 30 Days of Night is certainly more sober and respectable than most of the dreck that passes as horror these days; as the latest addition to the vampire genre, it’s a case of the emperor’s new clothes in which the clothes this time around are heavy winter outerwear.

True to the comic, 30 Days of Night comes to a bittersweet conclusion, adhering to its themes of macho sacrifice and love regained and lost. In other words, it comes down to a fistfight between Josh Hartnett and Danny Huston that ends with yet another variation of someone’s head getting disconnected from his trunk. “Next time they’ll take out Point Hope, Wainwright,” a character intones breathlessly at one point — not exactly the type of thought that sends shivers of dread down your usual moviewatcher’s spine. As a horror movie, 30 Days of Night is certainly more sober and respectable than most of the dreck that passes as horror these days; as the latest addition to the vampire genre, it’s a case of the emperor’s new clothes in which the clothes this time around are heavy winter outerwear.