3:10 to Yuma (2007, Dir. James Mangold):

3:10 to Yuma (2007, Dir. James Mangold):

Alice Evans: Ben Wade has a gang and they’re out there tonight, somewhere.

Dan Evans: If I don’t go, we gotta pack up and leave. Now I’m tired, Alice. I’m tired of watching my boys go hungry. I’m tired of the way that they look at me. I’m tired of the way that you don’t.

Critics didn’t really know what to make of James Mangold’s 1996 film Copland, aside from the fact that it was the film wherein Sly Stallone took a stab at actual “acting” [pronounced with airy English accent]. Most likely they looked at the cast list, which included Robert DeNiro, Ray Liotta and Harvey Keitel, and pegged it as a gritty film about the mean streets, and were left scratching their heads at the operatic shoot-em-up finale. Despite its glances at naturalism, Copland was essentially a Western, High Noon transplanted to the Jersey burbs, and while it didn’t necessarily cohere as anything beyond a series of gestures (a drunk, self-pitying Stallone listening to Springsteen’s “Stolen Car”? A bit too on-the-nose there), it had a certain gravitas to it that stuck with me after I left the theater, a sincerity in the telling.

Mangold hasn’t necessarily progressed as a director since then, but he brings those same qualities to bear on the remake of 3:10 to Yuma, a true rabble-rousing Western this time, and it’s now clear that Copland’s spiritual predecessor wasn’t High Noon but the original 1957 version of 3:10 with Glenn Ford and Van Heflin. The set-up, based on the Elmore Leonard short story, is simplicity itself: charming outlaw Ben Wade (Ford in the original, Russell Crowe here) is caught by the local authorities, who plan to haul him off to state prison on the titular train, but with Wade’s gang lurking nearby and ready to take out anyone who attempts to get Wade on the train, it falls on beleaguered but upright rancher Dan Evans (Christian Bale) to take responsibility, and earn some much-needed cash in the process.

Mangold hasn’t necessarily progressed as a director since then, but he brings those same qualities to bear on the remake of 3:10 to Yuma, a true rabble-rousing Western this time, and it’s now clear that Copland’s spiritual predecessor wasn’t High Noon but the original 1957 version of 3:10 with Glenn Ford and Van Heflin. The set-up, based on the Elmore Leonard short story, is simplicity itself: charming outlaw Ben Wade (Ford in the original, Russell Crowe here) is caught by the local authorities, who plan to haul him off to state prison on the titular train, but with Wade’s gang lurking nearby and ready to take out anyone who attempts to get Wade on the train, it falls on beleaguered but upright rancher Dan Evans (Christian Bale) to take responsibility, and earn some much-needed cash in the process.

The original 3:10 to Yuma was a chamber piece, as Ford and Van Heflin were mainly confined to a hotel room, the bad man heckling, taunting, and attempting to seduce the good man. It didn’t pretend to be anything other than a tightly-wound potboiler of a Western, and was economic in form and style. Mangold has loftier goals in mind with this remake; it’s been years since we’ve had the pleasure of a cracking good Western (not counting idiosyncratic treasures like Dead Man and The Proposition), and he is determined to resuscitate the genre in all its parched glory. So he cracks the story open to include more painterly vistas and hectic action setpieces, including a nighttime showdown with a trio of Injuns and a running battle down train tracks, which add the illusion of breadth if not depth. The dialogue is fearless in its adherence to the laconic conventions of the genre (“I’ve always liked you Byron, but even bad men love their mommas”) — it’s like the word “revisionism” never existed. The score by Marco Beltrami, all eerie strings and stinging electric guitars, hearkens to Ennio Morricone circa 1969, all but daring us to consider this film among the classics that revitalized the genre.

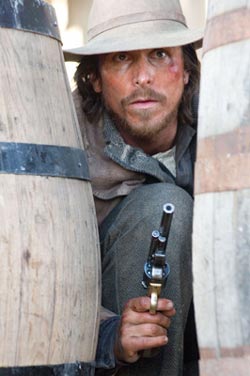

Certainly the actors are as worthy as any that have been in a Western. Even the minor roles are filled out nicely, especially Peter Fonda as a grizzled, “ain’t got time to bleed” bounty hunter, and a feral Ben Foster as Charlie, Ben’s ultra-loyal second-in-command. Bale’s Dan Evans is the nominal hero, but Mangold stacks the deck against him: hobbled with a false leg thanks to a Civil War shooting accident, unable to protect his ranch against the rapacious landowners who want to take it over, lacking the respect or even the sympathy of his teenage son (Logan Lerman), he might as well have a “kick me” sign nailed to his back. It’s up to Bale to rescue the character from complete martyrdom with his mesmerized, entranced acting style, and he does, just barely. Too bad he’s pitted against Crowe’s Wade, which is akin to matching up a newborn puppy against a rottweiler. Wade is a pure Hollywood creation, a gentleman scoundrel just at home killing off one of his own gang to save his own skin as he is sketching a bird in his notebook, or quoting Scripture. Like Hannibal Lector, he is only threatening when he’s threatened, erupting into violence faster than a race car accelerating to 60, and yet we’re asked to believe that he has the silky magnetism to reduce Evans’ steadfast wife (Gretchen Mol) to a swoon with a single line about her green eyes. Crowe recognizes the absurdity of all this and luxuriates in it, yet stops just short of sending the character up — sly, bemused, and alert with danger, he turns in his best performance in years, a welcome change from his recent “noble and agonized” roles in Cinderella Man and Gladiator.

Certainly the actors are as worthy as any that have been in a Western. Even the minor roles are filled out nicely, especially Peter Fonda as a grizzled, “ain’t got time to bleed” bounty hunter, and a feral Ben Foster as Charlie, Ben’s ultra-loyal second-in-command. Bale’s Dan Evans is the nominal hero, but Mangold stacks the deck against him: hobbled with a false leg thanks to a Civil War shooting accident, unable to protect his ranch against the rapacious landowners who want to take it over, lacking the respect or even the sympathy of his teenage son (Logan Lerman), he might as well have a “kick me” sign nailed to his back. It’s up to Bale to rescue the character from complete martyrdom with his mesmerized, entranced acting style, and he does, just barely. Too bad he’s pitted against Crowe’s Wade, which is akin to matching up a newborn puppy against a rottweiler. Wade is a pure Hollywood creation, a gentleman scoundrel just at home killing off one of his own gang to save his own skin as he is sketching a bird in his notebook, or quoting Scripture. Like Hannibal Lector, he is only threatening when he’s threatened, erupting into violence faster than a race car accelerating to 60, and yet we’re asked to believe that he has the silky magnetism to reduce Evans’ steadfast wife (Gretchen Mol) to a swoon with a single line about her green eyes. Crowe recognizes the absurdity of all this and luxuriates in it, yet stops just short of sending the character up — sly, bemused, and alert with danger, he turns in his best performance in years, a welcome change from his recent “noble and agonized” roles in Cinderella Man and Gladiator.

When the film truly gets cracking during the long windup to the final showdown, Crowe and Bale strike some very tangible sparks off each other, the former tickled and faintly puzzled by the latter’s hangdog rectitude. Unfortunately it takes the bulk of the film to reach that duel of the souls, and the rest of the time we have to make do with a few solid if not spectacular shootouts, the sight of a CGI horse exploding, and a storyline crowded with incidents and characters that ultimately shortchange the conflict between the two leads. Some may take issue with the logic of Evans and Wade’s climactic decision; I would argue that the early hints are there, but the film lacks the focus necessary to develop those hints so that the climax of the film comes off less enigmatic and more inevitable. While Mangold knows how to handle his actors, he could use a little work in paring a story down to its essentials.

When the film truly gets cracking during the long windup to the final showdown, Crowe and Bale strike some very tangible sparks off each other, the former tickled and faintly puzzled by the latter’s hangdog rectitude. Unfortunately it takes the bulk of the film to reach that duel of the souls, and the rest of the time we have to make do with a few solid if not spectacular shootouts, the sight of a CGI horse exploding, and a storyline crowded with incidents and characters that ultimately shortchange the conflict between the two leads. Some may take issue with the logic of Evans and Wade’s climactic decision; I would argue that the early hints are there, but the film lacks the focus necessary to develop those hints so that the climax of the film comes off less enigmatic and more inevitable. While Mangold knows how to handle his actors, he could use a little work in paring a story down to its essentials.

Still, there’s no denying the thrill of the film’s last fifteen minutes, a non-stop gun battle that culminates in a scene of wholesale slaughter at the train depot, and reconciles Evans with his son. During the chaos we recognize what we love about Westerns — the collision of moral imperatives and straightforward action, crises of loyalty and justice boiled down to face-offs with six-shooters. The final scene’s sinewy energy nearly compensates for the hour and a half of muffled plotting that got us to this point, even as Crowe deflates any pomposity with a final jaunty whistle to his trusty steed. It’s clear that Mangold loves the Western, and as a genre project, everything about the new 3:10 to Yuma reeks class. In the end, though, the word “project” might be far too apt; the film is a slavish re-creation, handsome yet distant, like thunder passing by a few counties away.