Lost Highway (1997, Dir. David Lynch):

Lost Highway (1997, Dir. David Lynch):

“It’s a film made with a certain breezy contempt for audiences. I’ve seen it twice, hoping to make sense of it. There is no sense to be made of it.”

— Roger Ebert

I wasn’t really aware of it at the time, but it must have been inspired by, subconsciously anyway, the O.J. Simpson trial. And how O.J. Simpson’s mind had to be tricked, so that he could go out and play golf, rather than commit suicide for the deed he did.

— David Lynch

Magician or charlatan, surrealist or nutjob: extremes rule the day when it comes to judging David Lynch. Those with fond memories of Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet (and even Wild at Heart) will be forgiving of the master — others with nightmares of Eraserhead or Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me will scoff and dismiss. I myself vacillate, film by film. When Lynch is on, he synthesizes dread, absurdism, genre tropes, and honest emotionalism like few other directors. When he’s off, he becomes an overdetermined, tawdry parody of himself (see the misplaced Wizard-of-Oz-meets-Elvis-in-Hell shenanigans of Wild at Heart, for example).

Examined within the context of Lynch’s career (especially 2001’s Mulholland Dr., which stands as the perfect summation of his work to date), Lost Highway (1997) plays like a free-jazz riff similar to the one morose saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) unleashes early on in the picture — that is, at once furiously concentrated and all over the place. Anyone with even a glancing knowledge of Lynch’s work will see his fingerprints everywhere: a murdered woman; colorfully vulgar psychopaths; deadpan humor that hits home a beat or two later than it ordinarily would; the sense of malign, otherworldly forces at work. Lost Highway doesn’t have Mulholland Dr.‘s discipline or cumulative power, but when it succeeds, it reminds us why we can always do with a little Lynch-ing.

Examined within the context of Lynch’s career (especially 2001’s Mulholland Dr., which stands as the perfect summation of his work to date), Lost Highway (1997) plays like a free-jazz riff similar to the one morose saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) unleashes early on in the picture — that is, at once furiously concentrated and all over the place. Anyone with even a glancing knowledge of Lynch’s work will see his fingerprints everywhere: a murdered woman; colorfully vulgar psychopaths; deadpan humor that hits home a beat or two later than it ordinarily would; the sense of malign, otherworldly forces at work. Lost Highway doesn’t have Mulholland Dr.‘s discipline or cumulative power, but when it succeeds, it reminds us why we can always do with a little Lynch-ing.

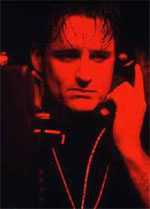

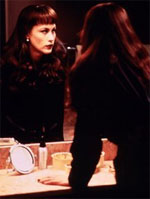

The film, which folds back on itself like a Moebius strip, begins with Fred and his brunette wife Renee (Patricia Arquette). Frozen in a clipped, loveless marriage (Fred keels over in agony when he is unable to “perform,” while Renee pats him like a forlorn dog and merely says, “It’s okay”), their lives are upended by a succession of unmarked, snowy videotapes that arrive on their doorstep. In a creepy harbinger of The Ring (the current Japanese horror wave owes a great deal to Lynch), the videos reveal the outside of Fred and Renee’s stucco house, followed by jump cuts to the interior, up the stairs, into their bedroom where they lay sleeping. Who is the filmmaker-intruder? All indications point to the Mystery Man (Robert Blake), who Fred meets at a party whilst Renee flirts with sleazy, pencil-mustachioed host Andy (Michael Massee). In the film’s most unnerving scene, the Mystery Man orders Fred to call his own house — and the Mystery Man answers the phone. In unison, both Mystery Men cackle, and the film’s major theme of dual, displaced personalities emerges.

The first 40 minutes of the film may well stand as Lynch’s finest cinematic achievement. With both languor and economy, he lays bare the implosion of a psyche, as the videotapes, Fred’s feverish visions, and off-kilter uses of mirrors and darkened spaces generate almost unbearable tension. Pullman is often dismissed as a lightweight actor, and many may deride his performance here as glowering and nothing more, but he hits all the right notes (no pun intended) as his sax-man rides the down escalator from bemused to broken. And so Fred ends up in prison for a murder he swears he didn’t commit, destined for the electric chair, besieged by headaches — but within the flash of a hallucinogenic montage, he is literally transformed … into hunky Pete Dayton (Balthazaar Getty), an unassuming mechanic.

The first 40 minutes of the film may well stand as Lynch’s finest cinematic achievement. With both languor and economy, he lays bare the implosion of a psyche, as the videotapes, Fred’s feverish visions, and off-kilter uses of mirrors and darkened spaces generate almost unbearable tension. Pullman is often dismissed as a lightweight actor, and many may deride his performance here as glowering and nothing more, but he hits all the right notes (no pun intended) as his sax-man rides the down escalator from bemused to broken. And so Fred ends up in prison for a murder he swears he didn’t commit, destined for the electric chair, besieged by headaches — but within the flash of a hallucinogenic montage, he is literally transformed … into hunky Pete Dayton (Balthazaar Getty), an unassuming mechanic.

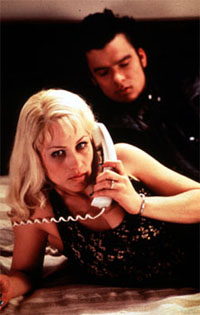

At this point, the plot reboots: Freed from prison and returning to his job at the auto shop (where Richard Pryor makes a distracting cameo), Pete runs afoul of gang boss Mr. Eddie (Robert Loggia) — or is his real name Dick Laurent? (Nearly every major character adopts and discards names and identities like cheap suits.) Soon Pete is involved with Mr. Eddie’s moll, Alice, who bears more than a passing resemblance to Renee in a platinum wig, and before long he spirals down into Lynch Land: porn rings, grotesque killings, visions of desert houses that explode and re-form themselves, doubles and displaced perversity. It takes pivotal reappearances by Andy and the Mystery Man to wrap the whole thing up, as much as a schizoid mess like this allows itself to be wrapped up.

It is clear where Lynch is going: Pete is a character invented by Fred’s disintegrating mind, a virile rough-houser who is the fulfillment of Fred’s wish fantasies, right down to getting the girl (Renee/Alice), but like the titular character of Alice in Wonderland, one must eventually reemerge from the rabbit hole, and thus Fred reappears, and the cycle begins anew. It would have worked if Lynch had invested the second half of the movie with the same craftsmanship and intensity that permeates the first half, but the longer the film runs, the slacker it gets. The actors make do with their sketchy characters, but few distinguish themselves. Getty is surprisingly charisma-free, channeling Charlie Sheen, of all actors. Bravely subjecting herself to the abuse that females in Lynch films must endure (no one else is as consistent at delineating the psychosexual hang-ups of callow male protagonists as he is), Arquette doffs her clothes and does her best to embody a fetishistic pin-up girl, not least during a strip scene performed at gunpoint. But she does herself no favors with her vacant stares and Bo-Beep voice; contrast that to the performances offered by Isabella Rossellini, Cheryl Lee, and Naomi Watts as other Lynchian ladies in peril. Loggia’s Mr. Eddie/Laurent has an amusing vignette with a tailgating driver, but is only a pale echo of Dennis Hopper’s landmark loony from Blue Velvet. You know that Lynch’s mind is elsewhere when he enlists the help of creepazoids like Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson on the film’s soundtrack — that’s like shoveling parody on top of parody. In the end, only Pullman and Robert Blake, giving his cryptic lines a terrific spin with his patented tough-guy attitude, rise completely above the murk. (Blake’s participation in the project is doubly ironic considering Lynch’s remark at the top of this essay.)

It is clear where Lynch is going: Pete is a character invented by Fred’s disintegrating mind, a virile rough-houser who is the fulfillment of Fred’s wish fantasies, right down to getting the girl (Renee/Alice), but like the titular character of Alice in Wonderland, one must eventually reemerge from the rabbit hole, and thus Fred reappears, and the cycle begins anew. It would have worked if Lynch had invested the second half of the movie with the same craftsmanship and intensity that permeates the first half, but the longer the film runs, the slacker it gets. The actors make do with their sketchy characters, but few distinguish themselves. Getty is surprisingly charisma-free, channeling Charlie Sheen, of all actors. Bravely subjecting herself to the abuse that females in Lynch films must endure (no one else is as consistent at delineating the psychosexual hang-ups of callow male protagonists as he is), Arquette doffs her clothes and does her best to embody a fetishistic pin-up girl, not least during a strip scene performed at gunpoint. But she does herself no favors with her vacant stares and Bo-Beep voice; contrast that to the performances offered by Isabella Rossellini, Cheryl Lee, and Naomi Watts as other Lynchian ladies in peril. Loggia’s Mr. Eddie/Laurent has an amusing vignette with a tailgating driver, but is only a pale echo of Dennis Hopper’s landmark loony from Blue Velvet. You know that Lynch’s mind is elsewhere when he enlists the help of creepazoids like Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson on the film’s soundtrack — that’s like shoveling parody on top of parody. In the end, only Pullman and Robert Blake, giving his cryptic lines a terrific spin with his patented tough-guy attitude, rise completely above the murk. (Blake’s participation in the project is doubly ironic considering Lynch’s remark at the top of this essay.)

Still, there’s no denying Lynch’s ability to combine sound and image to blood-curdling effect (Angelo Badalamenti’s soundtrack may well be his best for Lynch), and some of the most jolting moments (Blake’s face superimposed on Arquette’s body) have the pull of a nightmare. And then there are those shots of the lost highway at night, unspooling at supersonic speed while David Bowie croons “I’m deranged” over the title and end credits — the movie may end up exploded in a messy heap like that house in the desert, but the images underline the allure and danger of a Lynch film. All highways may come to dead ends, but the view from the driver’s seat is certainly enough to intoxicate along the way.