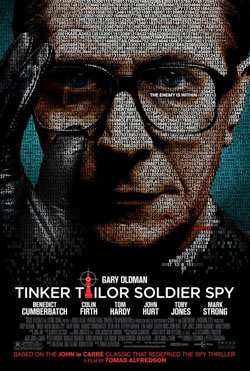

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011, Dir. Tomas Alfredson):

Arthur Conan-Doyle, Agatha Christie, Ian Fleming — does John le Carré now join the ranks of this august company when it comes to cinematic adaptations? Why not? Like the above authors, he captures a particular milieu (in his case, the skullduggery and tragedy of the Cold War), and like them, the mention of his name is enough to conjure whole atmospheres of incident and intrigue. Let the overgrown kiddies have Harry Potter — le Carré’s tales are decidedly for grown-ups, packed with intricacies of plot, character rosters that would do Dickens proud, and a gnomic dedication to its primary subject: the secret service as “the only real expression of a nation’s character.”

So why remake Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and why now? The original BBC miniseries of Tinker from the late 70s remains a television milestone, a heady collision of luck (filmed during the coldest winter England had seen in decades) and casting, with Sir Alec Guinness’s performance as George Smiley, the downtrodden senior spy with the mind of a bear trap, towering over it all. Like the shrinking matryoshka dolls in that series’ title sequence, the plot peels back layers of information to get at an essential kernel as Smiley, brought out of forced retirement, seeks out a mole buried deep in the heart of the “Circus” (aka the British Secret Service). The story’s pacing is a slap in the face to James Bond derring-do as Smiley, monk-like, gathers files and eyewitness accounts, reviews, interviews, and reflects, and yet we are enthralled because as his investigation draws closer and closer to the traitor, an entire vista opens up before us: a landscape of dashed British dreams of empire, curdled ambitions and loyalty for sale, strings pulled by a tawdry gang of liars and assassins who are not quite inhuman enough to play the game perfectly. Smiley’s chess match with Karla, his opposite number in the KGB, finds a fearful symmetry when personal and national betrayal are inextricably linked — in le Carré’s romantic world view, hearkening back to Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene, an adulterous affair carries the same weight as the stealing of government secrets. Guinness, ever-watchful, sometimes brusque, sometimes weary, embodies this dialectic, and by series’ end, this grandmaster of the game is reduced to asking his estranged wife a single pitiable question, one for which there can never be a satisfactory answer, and the final shot lingers on his face, bemused and bespectacled, forever one mystery short of fulfillment.

So why remake Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and why now? The original BBC miniseries of Tinker from the late 70s remains a television milestone, a heady collision of luck (filmed during the coldest winter England had seen in decades) and casting, with Sir Alec Guinness’s performance as George Smiley, the downtrodden senior spy with the mind of a bear trap, towering over it all. Like the shrinking matryoshka dolls in that series’ title sequence, the plot peels back layers of information to get at an essential kernel as Smiley, brought out of forced retirement, seeks out a mole buried deep in the heart of the “Circus” (aka the British Secret Service). The story’s pacing is a slap in the face to James Bond derring-do as Smiley, monk-like, gathers files and eyewitness accounts, reviews, interviews, and reflects, and yet we are enthralled because as his investigation draws closer and closer to the traitor, an entire vista opens up before us: a landscape of dashed British dreams of empire, curdled ambitions and loyalty for sale, strings pulled by a tawdry gang of liars and assassins who are not quite inhuman enough to play the game perfectly. Smiley’s chess match with Karla, his opposite number in the KGB, finds a fearful symmetry when personal and national betrayal are inextricably linked — in le Carré’s romantic world view, hearkening back to Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene, an adulterous affair carries the same weight as the stealing of government secrets. Guinness, ever-watchful, sometimes brusque, sometimes weary, embodies this dialectic, and by series’ end, this grandmaster of the game is reduced to asking his estranged wife a single pitiable question, one for which there can never be a satisfactory answer, and the final shot lingers on his face, bemused and bespectacled, forever one mystery short of fulfillment.

A tough act to follow — but with audiences thirsting for intelligent fare, and a new generation of moviegoers ready to be indoctrinated to the Circus, perhaps the time was ripe for a remake, much like each generation enjoys a different incarnation of Christie’s Poirot (this author is an Albert Finney man). Helmed by Swedish director Tomas Alfredson, best known for Let the Right One In, and with Gary Oldman assuming Guinness’s mantle as Smiley, the film’s pedigree is certainly nothing to sneeze at, and screenwriters Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan somehow compress the dense 500-page novel (and the seven-episode miniseries (later chopped down to six episodes for U.S. consumption)) into a two-hour narrative. Set in period (1973), the plot remains the same: a botched defection in Eastern Europe leads to the shooting of British agent Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong) and the ouster of Control (haggard John Hurt), the aged head of the Circus who is convinced a KGB mole has infiltrated the ranks. Flash forward a year, and Control’s right-hand man Smiley, forced to hit the bricks at the same time as Control, is called in by Minister Lacon (Simon McBurney with a hideous combover) to investigate a new lead that suggests that Control’s conspiracy theory was correct. Recruiting young “scalphunter” Peter Guillam (Sherlock‘s Benedict Cumberbatch), Smiley’s covert investigation focuses on the four men who have stepped to the fore since Control’s passing: Circus head Percy Alleline (Toby Jones), popular and womanizing Bill Haydon (Colin Firth), bearish Roy Bland (Cirian Hinds), and furtive “lamplighter” Toby Esterhase (David Dencik).

A tough act to follow — but with audiences thirsting for intelligent fare, and a new generation of moviegoers ready to be indoctrinated to the Circus, perhaps the time was ripe for a remake, much like each generation enjoys a different incarnation of Christie’s Poirot (this author is an Albert Finney man). Helmed by Swedish director Tomas Alfredson, best known for Let the Right One In, and with Gary Oldman assuming Guinness’s mantle as Smiley, the film’s pedigree is certainly nothing to sneeze at, and screenwriters Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan somehow compress the dense 500-page novel (and the seven-episode miniseries (later chopped down to six episodes for U.S. consumption)) into a two-hour narrative. Set in period (1973), the plot remains the same: a botched defection in Eastern Europe leads to the shooting of British agent Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong) and the ouster of Control (haggard John Hurt), the aged head of the Circus who is convinced a KGB mole has infiltrated the ranks. Flash forward a year, and Control’s right-hand man Smiley, forced to hit the bricks at the same time as Control, is called in by Minister Lacon (Simon McBurney with a hideous combover) to investigate a new lead that suggests that Control’s conspiracy theory was correct. Recruiting young “scalphunter” Peter Guillam (Sherlock‘s Benedict Cumberbatch), Smiley’s covert investigation focuses on the four men who have stepped to the fore since Control’s passing: Circus head Percy Alleline (Toby Jones), popular and womanizing Bill Haydon (Colin Firth), bearish Roy Bland (Cirian Hinds), and furtive “lamplighter” Toby Esterhase (David Dencik).

Alfredson is nothing if not an intelligent filmmaker, and some of his flourishes are inspired. Both Karla and Smiley’s wife, the twin poles of Smiley’s life that torment him, remain offscreen the entire movie, phantoms that he cannot come to grips with. A disastrous Christmas party at Circus headquarters that is referenced several times in flashback is a new addition to the narrative, and contains both spicy commentary (Circus employees singing the Soviet anthem and wearing Red Army costumes) and intertwined personal treachery. Alfredson also adroitly grounds the audience during the film’s constant shifts in time through simple devices such as the glasses Smiley wears — a detail that Spielberg himself would be envious of.

Bathing the film in beige and steel-gray tones, Alfredson embraces the fin de siécle rot of pre-Thatcher Britain, and Circus headquarters is a marvel of conference rooms that resemble beehives, dumb waiters and clanking elevators. In such a chilly atmosphere, the actors go all chilly too: while the dwarfish Jones is physically far from the Alleline described in the novel, the character’s ambition is as naked as ever via his snarled line deliveries, and Firth redeploys his usual tics (the furtive glances, the tight line of his mouth) in the service of a role that is all gamesmanship and no heart.

Bathing the film in beige and steel-gray tones, Alfredson embraces the fin de siécle rot of pre-Thatcher Britain, and Circus headquarters is a marvel of conference rooms that resemble beehives, dumb waiters and clanking elevators. In such a chilly atmosphere, the actors go all chilly too: while the dwarfish Jones is physically far from the Alleline described in the novel, the character’s ambition is as naked as ever via his snarled line deliveries, and Firth redeploys his usual tics (the furtive glances, the tight line of his mouth) in the service of a role that is all gamesmanship and no heart.

The bulk of the emotion is left to the bit players. Mark Strong is a fine Jim Prideaux; when we catch up with him in the incongruous setting of a boarding school in the English countryside (or perhaps not so incongruous, for what is the spy business but the bustling about of overgrown schoolboys with dreams of adventure?), Strong communicates Prideaux’s frail hold on sanity through tiny gestures: a hunch of his shoulders, a single hollow gaze. Cumberbatch’s Guillam is saddled with plot mechanics and negligible backstory, but he gets to cut loose in a scene in which he is forced to break up with his male lover. Best of all is Tom Hardy as Ricki Tarr, an agent on the run with crucial intel. Hardy is far more frazzled than Hywel Bennett’s Tarr in the BBC miniseries, and far more affecting — his tragic romance with KGB agent Irina (Svetlana Khodchenkova) occupies about 10 minutes of screentime, but a wordless moment between the two of them in a restaurant supplies the movie with a beating heart, speaking more volumes than much of the narrative.

“We are not so very different, you and I. We’ve both spent our lives looking for the weaknesses in one another.”

And that narrative is Tinker‘s fatal weakness — while its adherence to the novel’s path is admirable, it is simply impossible to present the story’s full breadth and scope in a few hours, and what we are left with is a Cliff’s Notes version short on connective tissue. Characters are disconnected and distant, or simply underused. (Avuncular Connie Sachs (Kathy Burke), a pivotal presence in the original series, is reduced to a dirty joke here.) It might have not mattered so much if Alfredson poured on the cinematic brio, but he is too wrapped up in the film’s elegaic tone to go for the jugular — a major disappointment considering how well he merged delicacy and brutality in Let the Right One In. Strangely enough, the BBC Tinker, suffused with an “everyone is watching” paranoia and bookended with an explosive start and finale, is more bracing — lento livened up with allegro passages, compared to Alfredson’s consistent adagio. The new Tinker‘s shortcomings are particularly obvious when it comes to the climax. With its bare, uncomplicated staging, the BBC version ratcheted up the suspense to near-unbearable levels, the revelation of the mole’s identity a kick to the gut; Alfredson gets lost in the shuffling from one dingy London location to another, and the unmasking of the mole occurs with a slow, almost demure pan of the camera — all the force of a sigh.

And that narrative is Tinker‘s fatal weakness — while its adherence to the novel’s path is admirable, it is simply impossible to present the story’s full breadth and scope in a few hours, and what we are left with is a Cliff’s Notes version short on connective tissue. Characters are disconnected and distant, or simply underused. (Avuncular Connie Sachs (Kathy Burke), a pivotal presence in the original series, is reduced to a dirty joke here.) It might have not mattered so much if Alfredson poured on the cinematic brio, but he is too wrapped up in the film’s elegaic tone to go for the jugular — a major disappointment considering how well he merged delicacy and brutality in Let the Right One In. Strangely enough, the BBC Tinker, suffused with an “everyone is watching” paranoia and bookended with an explosive start and finale, is more bracing — lento livened up with allegro passages, compared to Alfredson’s consistent adagio. The new Tinker‘s shortcomings are particularly obvious when it comes to the climax. With its bare, uncomplicated staging, the BBC version ratcheted up the suspense to near-unbearable levels, the revelation of the mole’s identity a kick to the gut; Alfredson gets lost in the shuffling from one dingy London location to another, and the unmasking of the mole occurs with a slow, almost demure pan of the camera — all the force of a sigh.

And what of Smiley? The casting of Oldman is like a dare: here is an actor who thrives on being volcanic, and Smiley is anything but. To his credit, he holds his own in Guinness’s shadow. He’s magnetic in a showstopping scene when he recalls an interrogation of Karla from younger days, and he’s clearly having a good time playing a man who holds his cards close to his chest. In the end, though, the Smiley in this Tinker is more an outline than a character, barely interacting with the other principals, and even Oldman’s savvy can’t quite close the distance between him and the audience.

Perhaps the key obstacle that Alfredson’s Tinker cannot overcome is its own slavish fidelity to the source material. Much like a Masterpiece Theatre production that hews too closely to a classic out of fear for offending the connoisseurs, the new Tinker is neatly pressed and presentable, but the clothes essentially remain the same. Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes and the contemporary BBC version of Sherlock starring Cumberbatch aren’t necessarily what you would want from a John le Carré remake, but their willingness to be creative with the original property and not devote themselves slavishly to the text could have been applied here. The film’s final montage, in which we receive glimpses of the fates of several major characters, and concludes with a sly slot of Smiley back home in the Circus, triumphant yet imprisoned, has an economy and playfulness that suggest what might have been. Next time, maybe we’ll get something that’s more pulse, less museum piece.