|

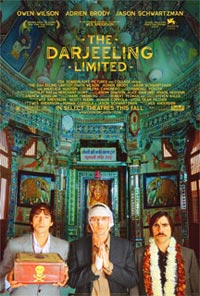

The Darjeeling Limited (2007, Dir. Wes Anderson):

Rita: What’s wrong with you?

Jack: I honestly don’t know. I’ll tell you the next time I see you.

Does Wes Anderson have a soul? The question seems to be a major preoccupation with critics. You can spot the technical eccentricities from a mile away: meticulously composed frames, eclectic soundtracks of sixties mod rock and undiscovered modern gems, precision-crafted production design that manages to be fussy and zany all at once. But even though his films are put down for being mannered larks that are too whimsical for their own good, what tends to stick to the memory are faces — perplexed faces mostly. Taking his cue from silent cinema, Anderson likes to get up close and personal with his characters, lingering over their mute distress, their indecision, their bewilderment. It helps that he also has a stock company of actors (Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, Anjelika Huston, Jason Schwartzman) who know exactly how to achieve major effects with the tiniest of expressions. Many derided Anderson’s last film, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, as too pleased with its own frippery, but the wackiness had a point to it: juxtaposed against this funhouse universe, Bill Murray’s mournful Steve Zissou gained weight, a soul.

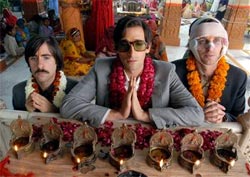

Those who aren’t convinced that there’s something honest and true going on behind the curtain will most likely not be convinced by The Darjeeling Limited, which nevertheless is both a recapitulation of, and a departure from, the Anderson method. Three brothers — Francis (Wilson), Peter (Adrien Brody) and Jack (Schwartzman) meet up on the titular train, ostensibly to make a spiritual pilgrimage across India on the anniversary of their father’s death. Each of them is nursing his own unspoken hurts and neuroses: Francis, his head swathed in bandages from a vague motorcycle accident, is the den mother, planning each activity out to the minute and insisting that everyone “say yes” to every experience; Peter, hogging all of the dead father’s personal belongings, is about to become a father and isn’t very happy about it, to the point that he hasn’t told his wife he’s coming out to India; Jack, still smarting from a recent breakup, is writing bitter autobiographical short stories (“The characters are all fictional,” he insists) and wandering around in bare feet like Paul McCartney on Abbey Road.

|

All the brothers are closed off to us as well as each other — in stark contrast to his previous films, Anderson lets them hoard their torments, and refuses to expose them as easy caricatures or cliches. As a result they come across as more whole, less stick-like. Communicating in implied threats and forced niceties, it seems highly unlikely they will reach any kind of rapprochement, and each gets pulled into their own private obsessions: Francis develops a fixation with locating a power adapter, Peter gets addicted to Indian cough syrup and buys a poisonous snake, and when he’s not playing mournful songs on his iPod, Jack is launching into an ill-advised affair with lovely steward Rita (Amara Karan), who may or may not be based on a certain Beatles song about a meter maid, but certainly fits the description.

Sounds like a typical Anderson film, right? Wealthy estranged families, deadpan absurdities, culture clash galore. Not exactly — as if tamed by the very real landscape that the train lumbers through, The Darjeeling Express settles into a lazy rhythm, not so desperate to get to the next visual punch line or bit of whimsy. This sometimes works to the movie’s detriment: the first half hour or so is composed of draggy conversations and awkward silences, with nary a hint of comedy or witty character interaction. But even here, Anderson is making a point — the harder the brothers attempt to buy into the privileged upper-middle-class American vision of spiritual uplift, the harder they fall on their faces. The title itself is indicative; there will be no bullet-train express to fulfillment for these folks, but instead a long, strung-out ride with destination unknown.

|

When the brothers are thrown off the train, left wandering the countryside with their father’s Louis Vitton suitcases in hand, the film slowly opens up, like a flower. Anderson doesn’t supply a necessarily deep or meaningful glimpse into rural India, but like all good travelers, Francis, Peter and Jack surrender their hope, and in the process stumble towards something resembling grace. A tragedy involving a village boy materializes out of the blue, and while other filmmakers might have milked it for obvious emotion, Anderson hangs back, letting the incident and its aftermath wash over the three men, drawing them closer in a nearly wordless passage as they are accepted as guests in a local community and invited to a funeral. As we sense that the film is drawing to a close, the story pulls one more card from its sleeve — a visit to a Christian monastery in the Himalayas, where the brothers’ mother Patricia (Anjelika Huston) has retreated to live as a nun. Patricia is a benevolent monster, but a monster nonetheless, and Huston gives the most devastating performance in the film, her maternal pooh-poohing failing to conceal her utter inability to relate to her children. And yet her suggestion to “meditate a bit” leads to a tour-de-force sequence in which the old Wes Anderson makes a brief appearance: jumping to different locales and characters in one continuous movement, like passing through numerous train compartments, we see all the people in the brothers’ lives, those left behind, living and wanting and wishing. Jarring and somehow right in its artificiality, the shot heralds an arrival at understanding and normalcy, and is capped off with a final mad dash to a train in which the brothers are forced to dump their metaphysical and literal baggage.

|

The actors are asked to navigate tricky emotional territory, with no lovable quirks to fall back on, and for the most part they do admirable jobs. It’s difficult to objectively judge Wilson’s performance given the recent tragedies in his life and their eerie similarities to the dire straits he’s in here, but there’s no doubt that he’s gained gravitas over the years. His famous broken nose hidden beneath a band aid, his bandaged face reduced to lips and eyes, he rises above his standard stoned hipster poses. Brody has the more internalized role, but he gets his turn to shine in a flashback to his father’s funeral in which his grief and dementia all but overwhelm the mechanic (Barbet Schroeder) entrusted with fixing his father’s car. Schwartzman struggles the most within the confines of his character (ironic given that he co-wrote the script with Anderson and Roman Coppola), and perhaps it’s fitting, as Jack is closer than the others to the typical conception of an Anderson hero — self-conscious, willful, almost petulant.

Clocking in at a modest 91 minutes, The Darjeeling Limited tells its story with a minimum of fuss, and gets out while the getting’s good. It might not be the best thing Anderson has done — that honor still goes to Rushmore — but none of his previous endings have the wry charm this one has, as the three brothers settle in on yet another train. Earlier, on the original Darjeeling Limited, the three have been the typical ugly Americans, bemused at an offer of lime juice, smoking in a non-smoking compartment, antagonizing the steward who came to collect their tickets, immediately heading to the lunch car for cigarettes and a beer. Now they accept the lime juice with deference, respond politely to the steward — and immediately head to the lunch car for cigarettes and a beer. As we watch the lush Indian landscape outside the train unfold and the credits roll, we’re left with the winsome thought that as much as things change us, we are irreducible at heart, and somehow we are okay with it.