The American (2010, Dir. Anton Corbijn):

The American (2010, Dir. Anton Corbijn):

I’m not very good with machines.

— George Clooney, The American

The American promises to be an escape from the machinations of the typical summertime action blockbuster — sure it has Hollywood’s most dependable leading man of the moment in George Clooney, and sure it has enough weaponry to satisfy the most discerning of arms fetishists, but its tone and intent harken back to paranoid thrillers of the ’70s, in which danger hangs around like a pungent mist, indefinable and therefore that much more chilling. Take for example the first five minutes of the film, which are literally as chilling as you can get: a sudden ambush on a frozen Swedish lake that culminates with Clooney putting a bullet in the head of the innocent woman he slept with the night before. No all-American hero here. Or is there? (Hold that thought.)

Martin Booth’s novel A Very Private Gentleman, upon which the screenplay is based, is a sleight-of-hand piece in which nothing and everything happens: we circle around the titular character as he hides out in a remote Italian mountain village, but despite his wry observations on the world and his courtly interactions with the locals, we ultimately learn very little about him except that he is an expert maker of assassination weapons and has good reason to be wary of everyone. Private and deadpan to the end, Booth’s gentleman skirts around anything that resembles human connection, and the book’s conclusion is like a mordant sigh, as our anti-hero escapes scott-free once again to continue his empty existence.

Anton Corbijn’s film version takes a different tack — as written by Rowan Joffe and essayed by Clooney, the American (whose name may be Jack or Edward or neither) is a bundle of raw nerves on the run from unknown assailants, a fine-tuned instrument on the verge of popping a spring. Although a quick-and-dirty chase is tossed into the middle of the story to ensure the audience is still awake, the filmmakers are more interested in the existential dread that shadows Clooney’s character wherever he goes, and as the camera rests its gaze on him, we read suspicion, paranoia, and weariness on his hooded countenance. And who can blame him? Corbijn places us by Clooney’s side as he isolates his star in the center of the frame, the world around him a suspicious blur from which all manner of peril might emerge.

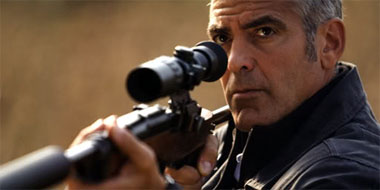

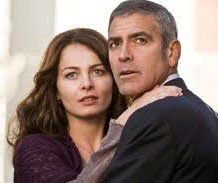

Still, this is Italy after all, the land of people and passions, and despite himself, the American is drawn into the lives of those around him: bemused interactions with the local priest who is out to save his soul (Paolo Bonicetti), faintly teasing repartee with his latest (and perhaps last) client Mathilde (Thekla Reuten), and most importantly, a half-guarded, half-passionate affair with a local prostitute named Clara (the aptly named Violante Placido). Juxtaposed against these detours into humanity is his latest job: the construction of a portable sniper’s rifle for Mathilde. The scenes in which Clooney whittles, fiddles, deconstructs and reconstructs the rifle with a craftsman’s ease are among the film’s best. Despite his protests to the contrary (see the quote up top), the American is more than adept with machines — he’s quite the slick piece of machinery himself. (In a puckish bit of humor, renowned photographer Corbijn has Clooney pose as a photojournalist, rather than as the butterfly collector in Booth’s novel).

Still, this is Italy after all, the land of people and passions, and despite himself, the American is drawn into the lives of those around him: bemused interactions with the local priest who is out to save his soul (Paolo Bonicetti), faintly teasing repartee with his latest (and perhaps last) client Mathilde (Thekla Reuten), and most importantly, a half-guarded, half-passionate affair with a local prostitute named Clara (the aptly named Violante Placido). Juxtaposed against these detours into humanity is his latest job: the construction of a portable sniper’s rifle for Mathilde. The scenes in which Clooney whittles, fiddles, deconstructs and reconstructs the rifle with a craftsman’s ease are among the film’s best. Despite his protests to the contrary (see the quote up top), the American is more than adept with machines — he’s quite the slick piece of machinery himself. (In a puckish bit of humor, renowned photographer Corbijn has Clooney pose as a photojournalist, rather than as the butterfly collector in Booth’s novel).

If you think the above suggests a simmering psychological study, you would be half-correct. In a welcome change from the excesses of most modern thrillers, Corbijn keeps things cool and elicits solid performances from his actors, his sinewy camerawork resisting the temptation to show off (save for a couple of gaudily lit nighttime shots that look like outtakes from U2’s latest album art). In the end, though, the story is too slight to convince as a character study, and overdone symbolism (tattoed and real butterflies make constant appearances) and clunky dialogue take hold, with the affable Bonicelli saddled with lines that belong in a late-period Godard film: “You are American. You think you can escape history. You live only for the present.” Clooney’s dogged (and hangdog) performance is credible, and it’s a pleasing thrill when the American begins to suspect that he may be constructing the instrument of his own doom, but Corbijn sidesteps the existential implications — and thus the thrust of Booth’s novel — in the latter half of the movie to focus on the doomed love between Clooney and Placido. Ah yes, the romantic fatalism of noir, what could be more American?

If you think the above suggests a simmering psychological study, you would be half-correct. In a welcome change from the excesses of most modern thrillers, Corbijn keeps things cool and elicits solid performances from his actors, his sinewy camerawork resisting the temptation to show off (save for a couple of gaudily lit nighttime shots that look like outtakes from U2’s latest album art). In the end, though, the story is too slight to convince as a character study, and overdone symbolism (tattoed and real butterflies make constant appearances) and clunky dialogue take hold, with the affable Bonicelli saddled with lines that belong in a late-period Godard film: “You are American. You think you can escape history. You live only for the present.” Clooney’s dogged (and hangdog) performance is credible, and it’s a pleasing thrill when the American begins to suspect that he may be constructing the instrument of his own doom, but Corbijn sidesteps the existential implications — and thus the thrust of Booth’s novel — in the latter half of the movie to focus on the doomed love between Clooney and Placido. Ah yes, the romantic fatalism of noir, what could be more American?