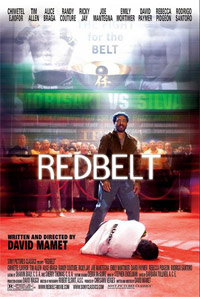

Redbelt (2008, Dir. David Mamet):

Redbelt (2008, Dir. David Mamet):

Let’s go to court … let’s go to Brazil … Insist on the move, insist on the move … Improve the position, improve the position … Breathe. Breathe. Look for a way out. There’s always a way out.

Couched in the vocabulary of mixed martial arts, the rhythms of the above quotation are rat-tat-tat, as you would expect in any action film concerning humans pummeling other humans, and yet in their insistence, their obsessive repetition, they could only have come from one man: David Mamet, playwright, film director, and black-belt jiu-jitsu artist. It seems almost shocking that Mamet has never tackled a film in the martial arts arena before — the idea of a ritualized confrontation between two men in a ring is a perfect counterpoint to Mamet’s verbal jousts, which are just as bruising as any physical combat.

But there’s more to Mamet’s work than conversational pugilism — he habitually undercuts his foul, fast-talking characters by plopping them in a funhouse of cons, feints, and trickery. In House of Games, The Spanish Prisoner, Spartan, and others, the verbal volleyball serves as the dense surface beneath which the machinations of plot, fate, and a cruel world threaten to overwhelm his heroes.

That fate awaits Mike Terry (Chiwetel Ejiofor), the easygoing yet focused jiu-jitsu instructor who’s not terribly keen on making money or entering official competitions; as he puts it, he doesn’t train people to win, he trains them to “prevail.” Married to nagging Sondra (Alice Braga), who dreams of making it in the fashion industry, Mike is content to skate by — until a chance encounter with strung-out lawyer Laura (Emily Mortimer) leads to a near-impossible accident in which the gun of one of Mike’s students, police officer Joe (Max Martini) is discharged, smashing the glass window of Mike’s establishment. In seemingly unrelated plot threads, Mike is sought after by shady fight promoter Marty Brown (Ricky Jay) as the undercard fighter in a match that could net him 50 grand, and also makes the acquaintance of just-past-his-prime actor Chet Frank (played by just-past-his-prime Tim Allen) when he defends him from some drunken hoods, leading to a job offer as a fight choreography consultant on Chet’s latest film, as well as an offer of financial assistance from his manager Jerry (Joe Mantegna).

That fate awaits Mike Terry (Chiwetel Ejiofor), the easygoing yet focused jiu-jitsu instructor who’s not terribly keen on making money or entering official competitions; as he puts it, he doesn’t train people to win, he trains them to “prevail.” Married to nagging Sondra (Alice Braga), who dreams of making it in the fashion industry, Mike is content to skate by — until a chance encounter with strung-out lawyer Laura (Emily Mortimer) leads to a near-impossible accident in which the gun of one of Mike’s students, police officer Joe (Max Martini) is discharged, smashing the glass window of Mike’s establishment. In seemingly unrelated plot threads, Mike is sought after by shady fight promoter Marty Brown (Ricky Jay) as the undercard fighter in a match that could net him 50 grand, and also makes the acquaintance of just-past-his-prime actor Chet Frank (played by just-past-his-prime Tim Allen) when he defends him from some drunken hoods, leading to a job offer as a fight choreography consultant on Chet’s latest film, as well as an offer of financial assistance from his manager Jerry (Joe Mantegna).

It doesn’t take a red belt or even a black belt to know something is rotten in the state of LA, and that the movie folks and the fight promoter folks are hungering for a pound of flesh. Redbelt‘s symbolism and theme are apparent from the very first image, in which two white marbles and one black marble are dropped into a hat — the fighter who chooses the black marble will be handicapped in the match (i.e., one arm tied behind his back). One is reminded of a shell game on the city streets, where the odds are stacked in the dealer’s favor every time. The questions Mike faces are who are the con men, and which of the balls is black?

It doesn’t take a red belt or even a black belt to know something is rotten in the state of LA, and that the movie folks and the fight promoter folks are hungering for a pound of flesh. Redbelt‘s symbolism and theme are apparent from the very first image, in which two white marbles and one black marble are dropped into a hat — the fighter who chooses the black marble will be handicapped in the match (i.e., one arm tied behind his back). One is reminded of a shell game on the city streets, where the odds are stacked in the dealer’s favor every time. The questions Mike faces are who are the con men, and which of the balls is black?

Mamet sprinkles plenty of red herrings and suspicious hints in the narrative — there’s the cocky magician (Randy Couture), a Brazilian fight promoter (Rodrigo Santoro) who happens to be Sondra’s brother, the faxing of a document of fighting rules that may or may not constitute property theft, a gold watch that might be stolen goods, and walk-on parts by Mamet standbys (David Paymer, Rebecca Pidgeon, Jay, Mantegna) as affable managers, cultured wives, sympathetic loan sharks. Yep, it’s as fishy as a salmon processing plant, and it’s saying something that Laura the lawyer turns out to be the most honest of the bunch.

Mamet is clearly plugged into the ideal of martial arts in its purest form: as a guide for living, a philosophical striving for nobility. For Mike, taking part in competition is defeat, and honoring the sanctity of the martial arts code is worth disgracing oneself (or in the case of one character, dying) for. Occupying nearly every frame of the movie, Ejiofor is the eye in the center of the storm, beleaguered, hustled, and eventually pounded, and yet never lacking in dignity. Mamet’s skills as a director have improved over the years; even though his environments and staging still have the whiff of the theater about them, he knows how to throw in nifty visual touches, as when the lights of a drug store wink off in the span of time it takes a wiper to move across a windshield, or when a vicious knife fight is presented from two perspectives — fast-cutting confusion when it happens, and fluid, almost balletic precision when it is viewed on a security camera tape in the aftermath.

Mamet is clearly plugged into the ideal of martial arts in its purest form: as a guide for living, a philosophical striving for nobility. For Mike, taking part in competition is defeat, and honoring the sanctity of the martial arts code is worth disgracing oneself (or in the case of one character, dying) for. Occupying nearly every frame of the movie, Ejiofor is the eye in the center of the storm, beleaguered, hustled, and eventually pounded, and yet never lacking in dignity. Mamet’s skills as a director have improved over the years; even though his environments and staging still have the whiff of the theater about them, he knows how to throw in nifty visual touches, as when the lights of a drug store wink off in the span of time it takes a wiper to move across a windshield, or when a vicious knife fight is presented from two perspectives — fast-cutting confusion when it happens, and fluid, almost balletic precision when it is viewed on a security camera tape in the aftermath.

Does it all hold together? Not quite. Once all the cards are played and the veil is parted, there are enough holes in the plot to riddle a slab of cheese, and for all the machinations, Mamet’s nervy way with language doesn’t come through very often. A few of the exchanges have the old Glengarry Glen Ross spice to them (“The fuck do I care?” is a common refrain), but Mamet is too busy manuevering his pawns into place to truly savor the dialogue. Normally one can enjoy the grace notes Mamet throws into his characters; here they’re all ciphers, and if no one seems trustworthy (even if they are), it’s because it’s difficult to trust blanks. Needless to say, Mike is forced into the ring, though not in the way you might expect, and the finale pits him against a world-class Brazilian fighter in an offstage brawl that loses him his 50 G’s but preserves his honor. After all, it’s not about winning, but doing the right thing, and the sentiment is a welcome antidote to the typical Hollywood ending in which the hero gets it all — too bad the ending is filmed like a low-rent Rocky, with everyone in the crowd, friend and foe and competitor alike, rising up as one to pay tribute to the honorable fighter, and you can be sure that a red belt will be involved. When the finishing move in the climax is cribbed straight from a Jackie Chan comedy, you have to roll your eyes a bit at the shlockiness of it all, which runs counter to Mamet’s otherwise bracing look at the games people play. “There is no situation that you can’t turn to your advantage,” Mike says early on, and by the end of Redbelt, that moral unfortunately sounds less than a sage piece of hard-earned wisdom than it does something that your typical action hero lunkhead would say.

Does it all hold together? Not quite. Once all the cards are played and the veil is parted, there are enough holes in the plot to riddle a slab of cheese, and for all the machinations, Mamet’s nervy way with language doesn’t come through very often. A few of the exchanges have the old Glengarry Glen Ross spice to them (“The fuck do I care?” is a common refrain), but Mamet is too busy manuevering his pawns into place to truly savor the dialogue. Normally one can enjoy the grace notes Mamet throws into his characters; here they’re all ciphers, and if no one seems trustworthy (even if they are), it’s because it’s difficult to trust blanks. Needless to say, Mike is forced into the ring, though not in the way you might expect, and the finale pits him against a world-class Brazilian fighter in an offstage brawl that loses him his 50 G’s but preserves his honor. After all, it’s not about winning, but doing the right thing, and the sentiment is a welcome antidote to the typical Hollywood ending in which the hero gets it all — too bad the ending is filmed like a low-rent Rocky, with everyone in the crowd, friend and foe and competitor alike, rising up as one to pay tribute to the honorable fighter, and you can be sure that a red belt will be involved. When the finishing move in the climax is cribbed straight from a Jackie Chan comedy, you have to roll your eyes a bit at the shlockiness of it all, which runs counter to Mamet’s otherwise bracing look at the games people play. “There is no situation that you can’t turn to your advantage,” Mike says early on, and by the end of Redbelt, that moral unfortunately sounds less than a sage piece of hard-earned wisdom than it does something that your typical action hero lunkhead would say.