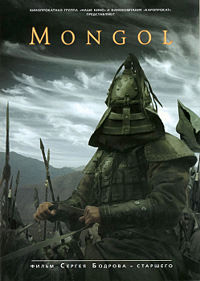

Mongol (2007, Dir. Sergei Bodrov):

Mongol (2007, Dir. Sergei Bodrov):

[or, “The Wrath of Khan”]

We’ve come a long way, baby. Or have we? In 1956 Howard Hughes took a stab at the Genghis Khan myth when he produced The Great Conquerer, which is generally acknowledged as the worst film John Wayne ever starred in. Filmed in Utah (where, as urban legend has it, radioactive soil caused the eventual deaths of Wayne and dozens of other crewmembers to cancer), burdened with the, ahem, unusual sight of John Wayne playing the great Mongol in a Fu Manchu mustache, The Great Conquerer belongs squarely in the “so bad it’s hilarious” category of shlock moviemaking, and we haven’t even mentioned Susan Hayward as a spirited Mongol highlander.

Flash forward half a century later, and in our search for the latest exotic, far-flung, mystical land to canonize, the wheel has spun around to land on Mongolia once again. So instead of a big-budget Hollywood production starring a Caucasian cowboy as the Khanmeister, we get a joint Russian-Khazakstan-Mongolia production helmed by a German, with a Japanese man (Asano Tadanobu) as the Khanmeister. It’s progress of a sort, I guess.

The film starts promisingly: it is the 12th century, in the border country of Tangut, and a lone man sits in a dank prison cell. The harsh strains of Mongolian throat music blend with the requisite symphonic score on the soundtrack as we’re taken back to the steppes of Mongolia 20 years before, when the man is a 9-year old named Temudgin (Odnyam Odsuren), being groomed by his father Eusegi (Ba Sen), the local khan, for an arranged marriage to a chieftain’s daughter.The plan goes awry when Temudgin’s heart is stolen by the willful, free-spirited Borte (Bayartsetseg Erdenebat), and a marriage pact is made. When Eusegi is poisoned by a rival clan, his former tribesmen take advantage of the situation, imprisoning Temudgin and awaiting the day he becomes a man so they can kill him, as custom dictates. With that setup, we’re off and running, ready for a tale of “revenge is best served hot.”

The film starts promisingly: it is the 12th century, in the border country of Tangut, and a lone man sits in a dank prison cell. The harsh strains of Mongolian throat music blend with the requisite symphonic score on the soundtrack as we’re taken back to the steppes of Mongolia 20 years before, when the man is a 9-year old named Temudgin (Odnyam Odsuren), being groomed by his father Eusegi (Ba Sen), the local khan, for an arranged marriage to a chieftain’s daughter.The plan goes awry when Temudgin’s heart is stolen by the willful, free-spirited Borte (Bayartsetseg Erdenebat), and a marriage pact is made. When Eusegi is poisoned by a rival clan, his former tribesmen take advantage of the situation, imprisoning Temudgin and awaiting the day he becomes a man so they can kill him, as custom dictates. With that setup, we’re off and running, ready for a tale of “revenge is best served hot.”

Mongol is essentially a superhero origin story, as we witness Temudgin’s transformation into the cunning strategist, romantic figure, national leader, and ferocious warrior we all know and love. Packed with incident and narrative, the plot rockets from point A to point Z at breakneck speed; you would probably get whiplash if you turned your head away from the screen for a moment. And therein lies the problem. Batman Begins came to mind more than a few times as I was watching: both films chronicle the painful education of a hero, and both suffer from similar pacing issues. Each scene plays out briskly, and the editing rhythms get same-y after a while. When Temudgin is reunited with Borte (Khulan Chuluun) as an adult, we’re meant to swoon at the passion of it all, but when we cut away to marauding horsemen as soon as the couple share a single kiss, how can we work up any heat?

Mongol is essentially a superhero origin story, as we witness Temudgin’s transformation into the cunning strategist, romantic figure, national leader, and ferocious warrior we all know and love. Packed with incident and narrative, the plot rockets from point A to point Z at breakneck speed; you would probably get whiplash if you turned your head away from the screen for a moment. And therein lies the problem. Batman Begins came to mind more than a few times as I was watching: both films chronicle the painful education of a hero, and both suffer from similar pacing issues. Each scene plays out briskly, and the editing rhythms get same-y after a while. When Temudgin is reunited with Borte (Khulan Chuluun) as an adult, we’re meant to swoon at the passion of it all, but when we cut away to marauding horsemen as soon as the couple share a single kiss, how can we work up any heat?

There’s plenty of combat, of course, and the battle scenes, replete with CGI weather effects and arterial blood sprays, should satisfy most slaughterhounds. Better still is Sun Honglei as Jamukha, Temudgin’s blood brother and eventual greatest rival for control of the burgeoning Mongolian empire. Of all the actors, Sun seems to be the only one who is aware that this is all a bunch of hooey; armed with a proto-punk buzzcut that is sharper than any blade wielded in the film, he chews the scenery to pieces, his wry little twists of the head and musical mutterings serving as punchlines. But best of all is an almost anecdotal passage in which a Chinese monk attempts to help the imprisoned Temudgin by transporting a bone necklace charm to Borte. As the monk wordlessly crosses mountains and deserts on foot, dogged in his determination even as his body slowly fails, one finally catches the whiff of genuine mythmaking.

Unfortunately, in a film that is all about myth creation, that’s as much as you’re going to get. In its rush to present the life and times of the Khan, critical events are glossed over or deleted completely. One moment Temudgin is a nomad on the run from his treacherous former tribesmen; the next he has a clan of his own. At one point he is a fugitive from the Tangut Kingdom with nothing to his name; the next he has assembled an army for a St. Crispin’s Day moment vs. Jamukha’s numerically superior forces. Bounced from event to event like a ping-pong ball, this Genghis is a cipher. Tadanobu Asano is a fine, quirky actor who’s best in roles that take advantage of his natural reticence; as Temudgin, he manages to be soulful and noble, but the script allows him to be little else. Khulan Chuluun fares slightly better as Borte – if it’s a good thing to be “better” when you’re playing the straitjacketed role of dutiful, ever-faithful wife.

Unfortunately, in a film that is all about myth creation, that’s as much as you’re going to get. In its rush to present the life and times of the Khan, critical events are glossed over or deleted completely. One moment Temudgin is a nomad on the run from his treacherous former tribesmen; the next he has a clan of his own. At one point he is a fugitive from the Tangut Kingdom with nothing to his name; the next he has assembled an army for a St. Crispin’s Day moment vs. Jamukha’s numerically superior forces. Bounced from event to event like a ping-pong ball, this Genghis is a cipher. Tadanobu Asano is a fine, quirky actor who’s best in roles that take advantage of his natural reticence; as Temudgin, he manages to be soulful and noble, but the script allows him to be little else. Khulan Chuluun fares slightly better as Borte – if it’s a good thing to be “better” when you’re playing the straitjacketed role of dutiful, ever-faithful wife.

Mongol does exactly what it intends to do; it serves as the launching pad for a sequel or two (the end of the film practically begs for the subtitle “To be continued…”), and does it with what passes for epic style these days – a few monumental vistas, a few faces covered with grit, a few shouts of anger and slashes of sword, appropriate swells of music on the soundtrack, and a storyline that would snuggle comfortably inside a comic (Conan the Barbarian, anyone?). But whatever your reaction to the film, you can still marvel at the magnificent scenery and dream your own dream of a epic that would be more intimate and substantial than what we see on screen. We’ve come a long way, baby.