Dirty Ho (1979, Dir. Lau Kar-Leung)

Dirty Ho (1979, Dir. Lau Kar-Leung)

“You haven’t lived until you’ve fought Dirty Ho … and then you’re dead!”

— Original tagline for Dirty Ho

[Originally reviewed for the 2006 Asian American Film Festival]

Given the recent “ascension” of martial arts films to art-house popularity (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero, House of Flying Daggers), watching this film is a useful lesson in kung fu history — and we’re not talking about the chop-sockies that populate after-hours TV, or the films of Bruce Lee, which stand apart and inimitable, or the clownish acrobatics of Jackie Chan. Dirty Ho (faithfully translated, the title’s meaning is closer to “Rotten Head Ho,” but admittedly it isn’t as fun as “Dirty Ho”), in its unassuming way, is actually a seminal work in martial arts film, bridging the gap between the genre’s stylized, theatrical origins and the frenetic, physical affairs of modern-day practitioners like Chan and Jet Li.

Director Lau Kar-Leung may not be familiar outside fanboy circles — he’s best known in the West for his pivotal supporting role in Chan’s Drunken Master II (aka The Legend of Drunken Master) — but his influence on kung fu movies is indisputable. From the 70s to the early 80s he helmed (and acted in) classics such as Executioners of Shaolin (1976), Mad Monkey Kung Fu (1979) and Eight Diagram Pole Fighter (1982), and under his watch the genre became something more than a wooden exhibition of pomp and pugilism. In opposition to the formality of King Hu, the godfather of modern martial arts cinema, he injected his films with a canny mix of ferocity and wit that few have equaled since. Even a relatively light confection like Dirty Ho is shot through with exhaustive and exhausting choreography, and while the combat in this film may seem dated to some eyes, there is no denying its inventiveness, or the impact it has had on more recent filmmakers such as Chan (or even Stephen Chow, who shares Lau’s fondness for hapless ne’er-do-wells who morph into super-fighters without quite losing their flawed, humane qualities — see King of Beggars and Kung Fu Hustle for proof).

Director Lau Kar-Leung may not be familiar outside fanboy circles — he’s best known in the West for his pivotal supporting role in Chan’s Drunken Master II (aka The Legend of Drunken Master) — but his influence on kung fu movies is indisputable. From the 70s to the early 80s he helmed (and acted in) classics such as Executioners of Shaolin (1976), Mad Monkey Kung Fu (1979) and Eight Diagram Pole Fighter (1982), and under his watch the genre became something more than a wooden exhibition of pomp and pugilism. In opposition to the formality of King Hu, the godfather of modern martial arts cinema, he injected his films with a canny mix of ferocity and wit that few have equaled since. Even a relatively light confection like Dirty Ho is shot through with exhaustive and exhausting choreography, and while the combat in this film may seem dated to some eyes, there is no denying its inventiveness, or the impact it has had on more recent filmmakers such as Chan (or even Stephen Chow, who shares Lau’s fondness for hapless ne’er-do-wells who morph into super-fighters without quite losing their flawed, humane qualities — see King of Beggars and Kung Fu Hustle for proof).

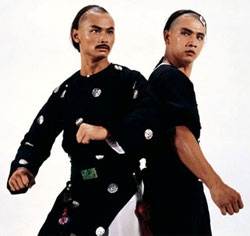

But Lau is also adept at working within formulas to tell engrossing stories. Dirty Ho plays a neat balancing trick between decorum and all-out martial arts insanity, and the balance is personified by Lord Wang Qinqin (the redoubtable Gordon Lau), by all appearances a cultured wine dealer but secretly the gifted 11th son of the Chinese emperor. Content to while away his time entertaining the ladies, sipping the finest wines, and admiring art, his placid lifestyle is interrupted by Dirty Ho (Wang Yue), an uncouth trickster who enjoys showing off and throwing around his hard-earned (read: stolen) money. Their friendly rivalry touched off by a competition over maidens at a local brothel, Wang wastes no time in showing Ho who’s boss through some sly martial arts showdowns in which he subdues Ho without actually betraying the fact he knows any kung fu. Gordon Lau, who ordinarily might have been cast as Ho, brings a good deal of savvy to his role as Wang, his movements as refined as air, his playful smirks punctuation to the tricks he plays.

After one of the brothel maidens (under Wang’s “hidden” guidance) beats Ho down in an amusing face-off and injures his head with a poisoned blade (ergo, the literal title of the movie), the thrust of the film becomes clear: Ho, who lacks an ounce of comportment, must be brought to heel under the elegant tutelage of Wang, who promises to provide the antidote to Ho’s wounded head in exchange for indentured servitude. The twist of the callow youth being taught humility and kung fu by the wise veteran is a ploy that was perfected by Jackie Chan in the original Drunken Master (1978), but Lau does the conceit one better: preferring his life of anonymity, Wang refuses to let on that he knows any martial arts, and when one of his brothers sends assassins to dispatch him, he must fend them off without giving the game away to Ho. Thus we are treated to a simultaneously comic and thrilling pas de trois in which Wang must defend himself against two killers posing as wine merchants, even as the three of them pretend to be doing nothing more taxing than tasting wine, their furious battle to the death fought right under Ho’s nose. The highlight of the film, the scene speaks to the frission at the heart of all martial arts movies: the clash between the rigor and economy of martial arts, as ritualized as any ancient art (like, say, the niceties of a wine ceremony), and the sheer exuberance of bodies in motion, spinning, blocking, improvising, and striking with grace.

After one of the brothel maidens (under Wang’s “hidden” guidance) beats Ho down in an amusing face-off and injures his head with a poisoned blade (ergo, the literal title of the movie), the thrust of the film becomes clear: Ho, who lacks an ounce of comportment, must be brought to heel under the elegant tutelage of Wang, who promises to provide the antidote to Ho’s wounded head in exchange for indentured servitude. The twist of the callow youth being taught humility and kung fu by the wise veteran is a ploy that was perfected by Jackie Chan in the original Drunken Master (1978), but Lau does the conceit one better: preferring his life of anonymity, Wang refuses to let on that he knows any martial arts, and when one of his brothers sends assassins to dispatch him, he must fend them off without giving the game away to Ho. Thus we are treated to a simultaneously comic and thrilling pas de trois in which Wang must defend himself against two killers posing as wine merchants, even as the three of them pretend to be doing nothing more taxing than tasting wine, their furious battle to the death fought right under Ho’s nose. The highlight of the film, the scene speaks to the frission at the heart of all martial arts movies: the clash between the rigor and economy of martial arts, as ritualized as any ancient art (like, say, the niceties of a wine ceremony), and the sheer exuberance of bodies in motion, spinning, blocking, improvising, and striking with grace.

As the stakes rise and Wang and Ho’s odyssey takes them from their backwater town to an ambush in a mountain pass and finally a furious showdown within the Imperial Capital itself, Lau slips in plenty of throwaway gags — a bunch of kung-fu fakers that parody the protagonists of Crippled Avengers, inventive uses of ordinary props and even innocent bystanders as combat instruments, and a surreal encounter with the “Seven Bitters of the East River,” kung-fu experts who have a, um, feminine side. It all climaxes with two impressive setpieces as Wang and Ho must fight through a phalanx of spears and swords to reach the capital, and then battle three top-class fighters in a painstakingly choreographed finale in the Imperial Halls.

As the stakes rise and Wang and Ho’s odyssey takes them from their backwater town to an ambush in a mountain pass and finally a furious showdown within the Imperial Capital itself, Lau slips in plenty of throwaway gags — a bunch of kung-fu fakers that parody the protagonists of Crippled Avengers, inventive uses of ordinary props and even innocent bystanders as combat instruments, and a surreal encounter with the “Seven Bitters of the East River,” kung-fu experts who have a, um, feminine side. It all climaxes with two impressive setpieces as Wang and Ho must fight through a phalanx of spears and swords to reach the capital, and then battle three top-class fighters in a painstakingly choreographed finale in the Imperial Halls.

Rest assured, this film is loaded (or afflicted, some might say) with the conventions of many films from this era. The acting plays more along the lines of hyper-exaggerated Chinese opera than the naturalism Western audiences are more comfortable with, and the studio-bound locations can be a bit claustrophobic (a far cry from the lush budget and settings of Crouching Tiger, for instance). Nonetheless, the film uses its shaggy-dog demeanor to its advantage. No great truths revealed here, no pretensions of grandeur — just a tidy little tale told in high style, and there’s something to be said for a movie that doesn’t overstay its welcome. High art it is not, but in its refreshing unpretentiousness, its frisky dance on the border separating courtliness and anarchy, Dirty Ho reminds us what we enjoy about martial arts films in the first place, minus those art-house trappings, even as it points to the developments that have enlivened the genre in the past few decades. It helps when you have a kung fu pimp like Lau Kar-Leung at the steering wheel.

Comments

LardyRevenger

I believe the actual translation is "Old Rotten Cabbage-Headed Ho"