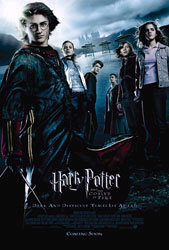

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005, Dir. Mike Newell):

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005, Dir. Mike Newell):

I approach the Harry Potter movies from what may be a different vantage point. I have read exactly one Potter novel (the first one), and am not immersed in the lore of the series, cannot bring you up to date on every event and winky-wink character name covered over thousands of pages. I’m not well-versed on the movie franchise either — I had seen the first and second entries in the series (you know, the bloodless, odorless, colorless ones directed by Chris Columbus), and was not annoyed, but not enthralled. On the other hand, I am no muggle pooh-poohing the quality (or lack thereof) of the books or movies — anything that can sit a kid still long enough to read a 700-page book is okay with me.

The Harry Potter storyline is a fanciful depiction of what it means to be royalty. With wizard blood in his veins, and gifted with powers he is only faintly aware of, Harry could be Prince Hal of ages past, feckless and unsure, counseled by ne’er-do-wells and secret associates as well as the bluest of blue bloods, locked by circumstances into a highfalutin destiny he may not necessarily want, looked upon by his peers with equal measures of awe and suspicion. As such, he is a remarkably passive character, the embodiment of every kid who ever felt helpless at the whim of adults whose motives are often veiled, or switch at the drop of a magical accoutrement. In other words, just about every kid alive, which goes a long way to explain the series’ success.

Even now, four movies into the saga, it strikes me how much those basic parameters remain unchanged. Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) is as likeably milquetoast as ever, his pal Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) still does a mean double take at every strangeness thrown his way, and Hermione (Emma Watson) still lectures and stamps her foot impatiently at how slow these boys are. Meanwhile, the resident profs of Hogwarts remain implacable, whether it’s prim-and-proper McGonagall (Maggie Smith), befuddled but secretive Dumbledore (Michael Gambon), or the mordant Snape (Alan Rickman). The special guest star this time out is Brendan Gleeson as Defense Arts Instructor Mad-Eye Moody, and he steals every scene he’s in with drunken, craggy charm. And of course there’s the usual helpings of Quidditch, the trials by fire, deceptions and mysteries, and another final confrontation where Harry is essentially ordered to follow the adults’ directions (be they alive or dead).

Even now, four movies into the saga, it strikes me how much those basic parameters remain unchanged. Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) is as likeably milquetoast as ever, his pal Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) still does a mean double take at every strangeness thrown his way, and Hermione (Emma Watson) still lectures and stamps her foot impatiently at how slow these boys are. Meanwhile, the resident profs of Hogwarts remain implacable, whether it’s prim-and-proper McGonagall (Maggie Smith), befuddled but secretive Dumbledore (Michael Gambon), or the mordant Snape (Alan Rickman). The special guest star this time out is Brendan Gleeson as Defense Arts Instructor Mad-Eye Moody, and he steals every scene he’s in with drunken, craggy charm. And of course there’s the usual helpings of Quidditch, the trials by fire, deceptions and mysteries, and another final confrontation where Harry is essentially ordered to follow the adults’ directions (be they alive or dead).

And yet, the contrast between this film and the first are remarkable. If nothing else, it’s fascinating to see what entropy has wrought on our cast of principals — once-reedy Radcliffe has filled and flattened out, while Grint, the original shrimp of the bunch, is now positively lanky (it helps that he’s cultivated the comic timing to make the most of his gangliness). Most intriguing is Watson, who seems to have entered the “quirky-beautiful” territory once inhabited by Anna Paquin. At times her scrunched-up face looks almost homely, and at other times it’s radiant. Fittingly enough, she seems closer to being an actual adult than the other two, and a fetching one at that.

And yet, the contrast between this film and the first are remarkable. If nothing else, it’s fascinating to see what entropy has wrought on our cast of principals — once-reedy Radcliffe has filled and flattened out, while Grint, the original shrimp of the bunch, is now positively lanky (it helps that he’s cultivated the comic timing to make the most of his gangliness). Most intriguing is Watson, who seems to have entered the “quirky-beautiful” territory once inhabited by Anna Paquin. At times her scrunched-up face looks almost homely, and at other times it’s radiant. Fittingly enough, she seems closer to being an actual adult than the other two, and a fetching one at that.

On a more substantive level, it’s heartening to see that Goblet of Fire thinks of itself as a movie, first and foremost. The Columbus entries in the series were loyal to the books to a fault, with a sameness to the pacing and tone that called to mind a school play with a Hollywood budget. The surfaces were sparkly, the big moments were carried off in workmanlike fashion, but it was all at a remove, like a dog-and-pony show. I’ve been informed that Goblet of Fire hews closely to the source material, but Mike Newell wisely grounds the flights of fancy in the tactile. Shot in grays and browns, this is a true Englander’s version of Potter’s world, where one can smell the mud and feel the pelting rain. It also helps that this is a pivotal chapter in the saga. Not only does the dread archenemy Voldemort (hammed up nicely by Ralph Fiennes) return, but Potter and crew face their sternest test yet: the onset of puberty. While the effects are more accomplished and the action is more visceral than ever (highlights include a airborne tussle with an onery dragon and a downright eerie underwater rescue), it’s the awkward ballroom dance lessons, the wizard proms, and the thwarted longings that stick to the memory. Newell may have seemed an odd choice for director coming on the heels of the visually gifted Alfonso Cuarón, who helmed Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban — after all, no one ever sang the visionary virtues of Newell’s Four Weddings and a Funeral or Notting Hill — but he is the right match for this material. Awkward romanticism is his stock-in-trade, and he takes care to linger over our heroes’ pubescent predicaments. Harry, Hermione, and Ron’s emotional discontent dovetails nicely with this episode’s underlying sense of menace; by the time the narrative expands to embrace horror, tragedy and pathos, Newell has earned the audience’s involvement. It’s a far cry from the self-satisfied, manufactured charm of the first two entries, and not a moment too soon.

I’ll leave it to the Potter-ites to obsess over the minutae — such as whether Dumbledore’s final eulogy packs the same tenor that it does in the book, or if Katie Leung is a suitable Cho Chang, who I’m told will become Harry’s main squeeze. (An aside: is it just me, or does it seem somewhat condescending that many critics are noting how “endearing” it is that a girl of Asian descent has a Scots accent? By that reckoning, I suppose we should be similarly smitten by Asian chicks who speak Valley Girl.) Aye, but there’s the rub. There’s those darn monolithic books to stay true to. Newell does a yeoman’s job of moving the proceedings along, but there’s still a touch of stodginess to it all — you can almost hear the pages turning. The first fifteen minutes in particular, in which Harry and friends are mysteriously attacked at a Quidditch tournament, are shot in disinterested fashion, as if Newell can’t be bothered to do much beyond regurgitating the book’s events. The most successful films based on novels introduce pleasures that you can’t necessarily glean from the written page. Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series brought an earthy specificity to Tolkien’s heroes and villains. John Huston’s Maltese Falcon gilded Dashiell Hammett’s tale with a veneer of cruelty. Newell’s primary spin on the source material is a surprising warmth in Radcliffe and Watson’s interactions that is only hinted at in the books. In contrast, Harry’s dalliance with Cho Chang is glossed over, undernourished. It seems almost unfair that the cinematic Harry and Hermione are not destined to be together, and that Hermione’s love interest will be bumbling, oafish Ron. I can imagine a freer universe — or at least, one not unilaterally controlled by J.K. Rowling — in which the smart, misunderstood girl finds love with the good-hearted, misunderstood prodigy, rather than the class clown. But alas, the order of things in this boarding school universe must remain undisturbed, and uneasy is the head that wears the crown. Like all good kings, Harry is fated for other things that may not be of his choosing. It’s to Newell’s credit that Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire conjures such feelings of dread, loss, and melancholy.

I’ll leave it to the Potter-ites to obsess over the minutae — such as whether Dumbledore’s final eulogy packs the same tenor that it does in the book, or if Katie Leung is a suitable Cho Chang, who I’m told will become Harry’s main squeeze. (An aside: is it just me, or does it seem somewhat condescending that many critics are noting how “endearing” it is that a girl of Asian descent has a Scots accent? By that reckoning, I suppose we should be similarly smitten by Asian chicks who speak Valley Girl.) Aye, but there’s the rub. There’s those darn monolithic books to stay true to. Newell does a yeoman’s job of moving the proceedings along, but there’s still a touch of stodginess to it all — you can almost hear the pages turning. The first fifteen minutes in particular, in which Harry and friends are mysteriously attacked at a Quidditch tournament, are shot in disinterested fashion, as if Newell can’t be bothered to do much beyond regurgitating the book’s events. The most successful films based on novels introduce pleasures that you can’t necessarily glean from the written page. Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series brought an earthy specificity to Tolkien’s heroes and villains. John Huston’s Maltese Falcon gilded Dashiell Hammett’s tale with a veneer of cruelty. Newell’s primary spin on the source material is a surprising warmth in Radcliffe and Watson’s interactions that is only hinted at in the books. In contrast, Harry’s dalliance with Cho Chang is glossed over, undernourished. It seems almost unfair that the cinematic Harry and Hermione are not destined to be together, and that Hermione’s love interest will be bumbling, oafish Ron. I can imagine a freer universe — or at least, one not unilaterally controlled by J.K. Rowling — in which the smart, misunderstood girl finds love with the good-hearted, misunderstood prodigy, rather than the class clown. But alas, the order of things in this boarding school universe must remain undisturbed, and uneasy is the head that wears the crown. Like all good kings, Harry is fated for other things that may not be of his choosing. It’s to Newell’s credit that Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire conjures such feelings of dread, loss, and melancholy.