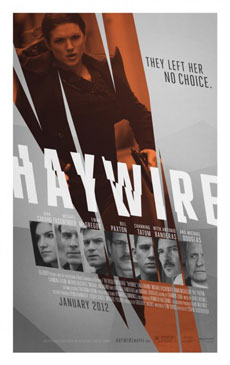

Haywire (2012, Dir. Steven Soderbergh):

Haywire (2012, Dir. Steven Soderbergh):

It’s not often that you get a simple either-or proposition when it comes to enjoying a movie, so ready yourself: whether or not you like Haywire comes down to whether you will like seeing Gina Carano, erstwhile mixed martial arts (MMA) fighter and all-around badass, kick around the starry likes of Ewan MacGregor and Michael Fassbender. Like we said, simple, no? Essentially a stunt (Steven Soderbergh, who never met a genre trope he didn’t like to play around with, wouldn’t have it any other way), the film takes its starting point from the Bourne movies (agent wronged and on the lam in gritty European locations, with bone-crunching fight scenes thrown in) and then injects all the trademark Soderbergh elements: jumps back and forth in time, a patina of hipster cool, characters slimmed down to existential ciphers, all of it filmed by Soderbergh himself in a riot of colors and jazzy edits that aspire to French New Wave. The fact that Carano, a first-time actor, is allowed to go toe-to-toe with thespians such as Michael Douglas and Antonio Banderas is part of the fun, or is that part of the joke? Hard to say, as the screenplay by frequent Soderbergh collaborator Lem Dobbs is way too arid to approach something resembling a real emotion. It’s difficult to work up a sweat or a genuine sense of dread when everything is a game from the start.

At least the formidable Carano is game enough — she doesn’t have the ability to lift the dramatic material, but when she goes to town on Channing Tatum in a brutal opening fisticuff that the rest of the film never quite equals, her physical grace is like quicksilver, briefly revving the movie to life. Among the slumming supporting actors, a slimy MacGregor gets to have the most fun, Banderas goes all mealymouthed as a hangdog operative with his own agenda, Michael Douglas gets reptilian (shocker) as a government boss, and Bill Paxton gets to play Carano’s Marine vet daddy, which plays into her character’s only nuance: she’s a Daddy’s Girl. Too bad even that nugget of potential is wasted in a showdown that refuses to up the ante.

Soderbergh has a chameleon-like fascination with genres, yet ever since The Limey he’s settled into a knowing groove for his thrillers; while he’s fond of playing with the syntax, he seems disinterested in the meat. Erase the gonzo sincerity that fuels the best pulp movies, and you’re left with smooth moves, slick camerawork, and little reason for being. By all means, be cool, be witty and be stylish — all of these things Soderbergh can handle in his sleep. But without the harsh tang of consequence as a counterbalance, Carano might just as well be a model posing on a runaway shaped like an MMA cage.