San Francisco is a town where you can catch a film festival virtually any day of the week, and as you would expect, these festivals run the gamut, from more-indie-than-indie fringe stuff, all the way to that self-congratulatory gargantuan that is the San Francisco International Film Festival (for a forever-in-progress look at a previous year’s fest, see my essay).

Nestling comfortably between these two extremes is the International Asian American Film Festival. Now entering its 24th year, and hopefully past the ups and downs of recent incarnations (last year’s offerings were a bit undernourished), this year’s festival has a healthy mix of newcomers and showcases — and far be it for me to deride a festival that can unearth a kung fu classic that contains my name in the title (Dirty Ho).

The phrase “Asian American” naturally brings up a host of interpretations and points for debate. What exactly does “Asian American” mean? How is that particular culture or consciousness defined? What is it allowed to include (films made in Asian Asia, for example)? These aren’t questions that will be answered by society any time soon, so the organizers of this event wisely let everyone in on the fun, everything from “pure” Asian cinema to politically and culturally relevant stuff grown here in the US.

I tend to gravitate towards the Asia-bred material at these festivals — maybe due to my stubborn allegiance to narrative-driven movies. Most of the pioneering work in Asian American film seems to be taking place in non-fiction realms (as it is with American cinema in general), and apart from the rare breakthrough such as Saving Face or Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle (yes, believe it), narrative triumphs seem to be few and far between, at least to these eyes.

It probably doesn’t help that most of my cinematic influences (Wong Kar-Wai, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Kurosawa, Taiwan New Wave) hail from the Far East. At their best, their works occupy a certain space in my head, and with their tone and pace, generate fresh ways of looking at environments, relationships, interconnections. Perhaps I’m subconsciously playing into the familiar stereotypes, the exoticism of difference. But if the world hasn’t figured it all this out yet, perhaps I can be similarly indulged …

So with that caveat dully noted, here’s my take on the films I’m seeing at this year’s festival.

|

Citizen Dog (Ma Nakorn) (2005, Dir. Wisit Sasanatieng)

“We can’t always find what we’re looking for, but sometimes, when we stop looking, those things find us.”

In my admittedly brief exposure to Thai cinema, I’ve looked for commonalities in storytelling and filmmaking style. I’ve seen strict crowd-pleasers (Ong Bak) as well as dreamy productions (Last Life in the Universe) and even the works of transplanted directors (the Pang brothers’ The Eye). All of these films evince a certain wit, a fluid facility with the camera, touches of the fantastic (Gabriel Garcia-Marquez style), and not a whole lot of staying power. Coming from a region in which nearly all other modes have been exploited (from the epic naturalism of China cinema to the hyperbolic fun of Hong Kong, the genre-mashing exploits of Japan and the emotionally direct dramas of Korea), perhaps Thai films are mapping more genteel territory. Their pleasures are of the elusive kind, like steam in a sauna. You certainly luxuriate in them while you watch them, but how much of it stays with you after it’s done?

|

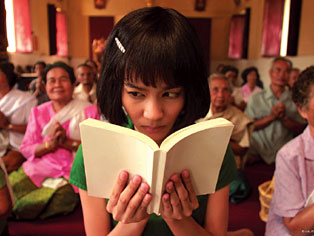

Case in point: Wisit Sasanatieng’s Citizen Dog, which has been hailed as “Chungking Express meets Amelie meets The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.” Certainly the synopsis would suggest as much. The plot (such as it is) follows the shambling exploits of Pod (Mahasamut Boonyarak), a country bumpkin trying to make it in the big city of Bangkok. Smitten with a maid named Jin (Saengthong Gate-Uthong) who has an obsession with neatness and a fetish for a “white book” that she cannot understand (it is written in Italian), Pod spends his waking hours taking on jobs (security guard, taxi driver) that place him closer to his object of desire. Bustling in the background of Pod’s life (and sometimes taking over the narrative completely) are the colorful denizens of the city: a motorcycle taxi driver who happens to be a ghost, a little girl who thinks and acts like she’s 21, a talking teddy bear given to bouts of depression and heavy drinking, an amnesiac businessman who compulsively licks everything he sees, and soap-opera characters in a magazine story that come to smudged Photoshop life. All this is presented with light absurdist touches (at one point Pod gets his finger chopped off, but shortly thereafter it pops back on, all of it presented as a bloodless CGI sight gag) as well as surreal setpieces (a mountain of plastic bottles that towers over downtown Bangkok, a downpour of falling motorcycle helmets). Throw in a few heartfelt folk-rock musical numbers that comment on the action, computer-brushed cinematography that bursts with rainbow colors, and even a cameo appearance by Village Voice film reviewer extraordinaire Chuck Stephens, and you have the very definition of “whimsy.”

|

One could dimiss Citizen Dog as a bunch of unrelated riffs, but under the candy-coated exterior is a very clear preoccupation with the city life, and its various sadnesses and pitfalls. “If you get a job in Bangkok, you’ll wake up with a tail wagging out your ass,” Pod’s crotchety grandmother warns him at the start of the film, and as the title implies, we all become dogs in the end, even if the tails are never actually seen in the movie. Otherwise, the film is rife with anthropomorphic wisecracks: sardines become tapping human fingers, humans cackle like geese or happily lick faces like mutts, and even Pod’s grandmother is reincarnated as a gecko. Pod’s unrequited love, Jin’s obsessive tendencies, the various neuroticisms of their town’s citizens — these all suggest the vagaries of life in the urban jungle, and its attendant loneliness and fractured sense of community. As Sasanatieng gently observes, everyone is busy seeking to become something they are not — such as the aforementioned girl and her woefully neglected teddy bear, a Chinese-Thai waitress who believes she is the descendent of a princess, or her boyfriend, who horns in on kids’ Chinese classes just so he can understand the language, or Jin, who descends into the madness of radical environmentalism based on a single mistaken encounter. At the center of this storm is Pod, played by Mahasamut with deadpan bemusement, observing the action but always at a remove from it, always the country boy who can’t fit in with the city, and thus, logically, the last resident in town without a “tail.”

|

Finally, Citizen Dog is about dreams, or the lack thereof. Pod is ridiculed for being a man “without a dream,” but by the end of the film, roles have been reversed, as Jin’s dream of being able to read the book ends in a tragic black joke, and the lovesick Pod hopes against hope for Jin to return his affections. Sasanatieng is most definitely on the side of the musicals, where technicolor splendor and true love conquer all, but while the production is near-flawless in its blending of real life and CGI gloss, the love story is perhaps the film’s least engrossing aspect, its desultory twists and turns a lead weight that eventually sinks the story’s final third. The obligatory happy ending seems tacked-on, an afterthought. But even as it evaporates before your eyes, Citizen Dog‘s cinematic invention, rambling warmth, and the sunny way in which it exposes its serious undercurrents suggests that there may indeed be some heat pulsing from the center of all that steam.