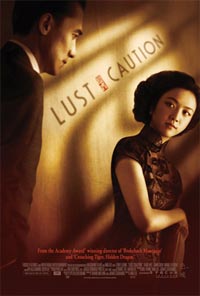

Lust, Caution (2007, Dir. Ang Lee):

Lust, Caution (2007, Dir. Ang Lee):

Though it was still daylight, the hot lamp was shining full-beam over the mahjong table. Diamond rings flashed under its glare as their wearers clacked and reshuffled their tiles. The tablecloth, tied down over the table legs, stretched out into a sleek plain of blinding white. The harsh artificial light silhouetted to full advantage the generous curve of Chia-chih’s bosom, and laid bare the elegant lines of her hexagonal face, its beauty somehow accentuated by the imperfectly narrow forehead, by the careless, framing wisps of hair. Her makeup was understated, except for the glossily rouged arcs of her lips. Her hair she had pinned nonchalantly back from her face, then allowed to hang down to her shoulders. Her sleeveless cheongsam of electric blue moire satin reached to the knees, its shallow, rounded collar standing only half an inch tall, in the Western style. A brooch fixed to the collar matched her diamond-studded sapphire button earrings.

— Eileen Chang, “Lust, Caution”

Ang Lee has comfortably staked out a niche for himself as a “prestige” filmmaker, and within that niche he’s involved himself with an impressive variety of genres. From his early indie days (Pushing Hands, The Wedding Banquet) to his period pieces (Sense and Sensibility, The Ice Storm) to his noble quest to make pulp safe for the arthouse masses (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, The Hulk), all his films are united by his personal style: measured, almost watery in its transparency, fluid, elegant, and very remote. It’s a canny strategy — when diving into topics that your heartland audience might find uncomfortable (gay cowboy love, spouse swapping, a pro-South Civil War drama, a subtitled action picture), it pays to hold your viewers by the hand and envelop them in the warm embrace of good taste. I find his work easy to admire and difficult to love.

After the unexpected success of Brokeback Mountain (that “gay cowboy movie”), what controversial subject could Lee utilize for a follow-up? An NC-17 film, as it turns out. Doubling back to his Chinese heritage, Lee has adapted the short story “Lust, Caution” by one of China’s foremost 20th-century writers, Eileen Chang. It’s easy to see the attraction to the source material — spies and lovers in 1940s Shanghai, frank sex scenes, the sultry scent of doomed love, the epic sweep of a period piece. Covering a period of four years, the story follows Wang Chia-chih (newcomer Wei Tang), a callow young actress who gets caught up in a plot to kill Mr. Yee (Tony Leung), a Japanese sympathizer who will one day become a minister in Shanghai’s puppet government during World War II. Encouraged by her revolutionary theater troupe buddies to play the part of a wealthy socialite named Ma Tai Tai to get close to Mr. Yee, it’s all a big game to Wang, but when true Chinese revolutionaries recruit her to infiltrate the Yee household, playacting blooms into a full-blown affair, and infatuation and divided loyalties take hold.

After the unexpected success of Brokeback Mountain (that “gay cowboy movie”), what controversial subject could Lee utilize for a follow-up? An NC-17 film, as it turns out. Doubling back to his Chinese heritage, Lee has adapted the short story “Lust, Caution” by one of China’s foremost 20th-century writers, Eileen Chang. It’s easy to see the attraction to the source material — spies and lovers in 1940s Shanghai, frank sex scenes, the sultry scent of doomed love, the epic sweep of a period piece. Covering a period of four years, the story follows Wang Chia-chih (newcomer Wei Tang), a callow young actress who gets caught up in a plot to kill Mr. Yee (Tony Leung), a Japanese sympathizer who will one day become a minister in Shanghai’s puppet government during World War II. Encouraged by her revolutionary theater troupe buddies to play the part of a wealthy socialite named Ma Tai Tai to get close to Mr. Yee, it’s all a big game to Wang, but when true Chinese revolutionaries recruit her to infiltrate the Yee household, playacting blooms into a full-blown affair, and infatuation and divided loyalties take hold.

Talk about this film has started and ended with the sex scenes, and although they stop short of actual hardcore, there are ample displays of genitalia. Certainly Eileen Chang didn’t emphasize any purple-prosed sex in her original story, but give Lee credit — he films the sex like combat, the two participants striving for power and domination over the other, their tug-of-war pushing the narrative on. On the other end of the spectrum, Yee perfectly dramatizes the effete warfare of a mah-jongg game, as Ma Tai Tai gains access to Mr. Lee’s life by playing with Mrs. Yee (a subtly devious Joan Chen) and her friends. Shooting their gaming contests with a flurry of cuts and overlapping rapid-fire dialogue, Lee exposes the raw animus underneath the small talk, where a single averted look spells guilt, complicity, secrecy. When in the midst of a game Mr. Yee reaches over for a snack in order to glimpse at a hastily scribbled telephone number, accepting an invitation to infidelity, it’s a moment thrilling in its simplicity and swiftness.

Talk about this film has started and ended with the sex scenes, and although they stop short of actual hardcore, there are ample displays of genitalia. Certainly Eileen Chang didn’t emphasize any purple-prosed sex in her original story, but give Lee credit — he films the sex like combat, the two participants striving for power and domination over the other, their tug-of-war pushing the narrative on. On the other end of the spectrum, Yee perfectly dramatizes the effete warfare of a mah-jongg game, as Ma Tai Tai gains access to Mr. Lee’s life by playing with Mrs. Yee (a subtly devious Joan Chen) and her friends. Shooting their gaming contests with a flurry of cuts and overlapping rapid-fire dialogue, Lee exposes the raw animus underneath the small talk, where a single averted look spells guilt, complicity, secrecy. When in the midst of a game Mr. Yee reaches over for a snack in order to glimpse at a hastily scribbled telephone number, accepting an invitation to infidelity, it’s a moment thrilling in its simplicity and swiftness.

Chang’s original story, for all its perceptive details and psychology, is essentially a romantic plea for forgiveness. Having discovered that she was married to a Japanese collaborator in real life, she concocted “Lust, Caution” as a sort of absolution: the woman, fully recognizing the immorality of the man, nevertheless sacrifices herself for love, while the man honors the woman by being devastated by the loss. The film follows this thread faithfully, right down to a breathless climax in the most innocuous of places, a jewelry shop. When the truth is revealed, the suddenness and finality of what happens next is like a kick to the stomach.

Chang’s original story, for all its perceptive details and psychology, is essentially a romantic plea for forgiveness. Having discovered that she was married to a Japanese collaborator in real life, she concocted “Lust, Caution” as a sort of absolution: the woman, fully recognizing the immorality of the man, nevertheless sacrifices herself for love, while the man honors the woman by being devastated by the loss. The film follows this thread faithfully, right down to a breathless climax in the most innocuous of places, a jewelry shop. When the truth is revealed, the suddenness and finality of what happens next is like a kick to the stomach.

However, Lee is less successful at wringing something truly unique out of this set-up. For all of the film’s stately pacing and class-A production values (’40s Shanghai never seemed quite so tangible), it takes more than half its running time to boil it down to its true essence, the contest between Lee and Chia-chih. Chang’s short story was a potboiler, but it also had a swinging, casual zing to its narrative and character byplay. Lee prefers to keep things tamped down, and although he offers up a few Hitchcockian shocks (a scene in which a man takes forever to die after being stabbed numerous times echoes Torn Curtain), and throws in a few laughs as the theater troupe, clearly in over their heads, get caught up with youthful enthusiasm as they embark on their terrible project, the mood soon sinks into one of glum inevitability. When one of the sex scenes is intercut with the barking of a guard dog outside the window, the symbolism of the moment veers dangerously close to cheese. Subtract the graphic sex scenes, and you are essentially left with a lushly photographed (by the ever-trusty Rodrigo Prieto) and scored (by Alexandre Desplat) melodrama, in which Lee stacks the chips in favor of the lovers — when given a choice between the magnetic Tony Leung and a revolutionary cadre of solemn, sexually inexperienced pretty boys (Lee-Hom Wang) and unfeeling bosses (Chung Hua Tou), is there really any choice at all? The details are there, the plot turns are there, and certainly the surface textures are there (the quotation that opens this essay is brilliantly transferred to film), but the ghost is missing from this shell.

As always, Lee elicits sensitive performances from his principals. Mr. Yee, burdened by encroaching middle age, fueled by bottomless rage, his emotions buried beneath waxen formality, could have easily descended into parody — just imagine the part played by Jeremy Irons, who would clench his jaw and furrow his eyebrows and work hard to make you feel the very harrowing of his being. Tony Leung, the smoothest and most understated of Hong Kong actors, takes the opposite approach, letting small smiles escape like flashes of lightning, his eyes going limpid or angry for milliseconds at a time. When he finally does explode, the effect is that of a window being thrown wide open, and Leung is unflinching in presenting Lee’s ugliness as well as sadness. Wei Tang does well with what is ultimately a cipher of a character — veering crazily from dowdy would-be actress to gussied-up seductress, she is believable as a seasoned player getting caught up in the play, but less so as an ordinary plebian who seems far too straitlaced and plodding to get caught up in fanciful spy games. Still, she deserves points for her fearlessness, and saves her best for last, when she must decide between duty and love in a matter of seconds.

As always, Lee elicits sensitive performances from his principals. Mr. Yee, burdened by encroaching middle age, fueled by bottomless rage, his emotions buried beneath waxen formality, could have easily descended into parody — just imagine the part played by Jeremy Irons, who would clench his jaw and furrow his eyebrows and work hard to make you feel the very harrowing of his being. Tony Leung, the smoothest and most understated of Hong Kong actors, takes the opposite approach, letting small smiles escape like flashes of lightning, his eyes going limpid or angry for milliseconds at a time. When he finally does explode, the effect is that of a window being thrown wide open, and Leung is unflinching in presenting Lee’s ugliness as well as sadness. Wei Tang does well with what is ultimately a cipher of a character — veering crazily from dowdy would-be actress to gussied-up seductress, she is believable as a seasoned player getting caught up in the play, but less so as an ordinary plebian who seems far too straitlaced and plodding to get caught up in fanciful spy games. Still, she deserves points for her fearlessness, and saves her best for last, when she must decide between duty and love in a matter of seconds.

You might think that Lust, Caution can be dismissed based on some of the criticisms above, scoffed at as just another Oscar-baiting film with the added draw of hot sex. Yet the film sticks with you; predictable and inevitable it may be, but Lee’s hothouse romanticism, and the final haunting image of an empty bed, are hard to shake. Perhaps it’s due to the pull of stories like these, the thrill of illicit activity and the tragedy of lovers that are fated to part. Lee knows that films are a dream machine, and he uses his dream machines as hypnotics, easing us into an absorbed mood as gently as slipping into a steambath. It adds up to movies like this one — easy to admire, difficult to love.

You might think that Lust, Caution can be dismissed based on some of the criticisms above, scoffed at as just another Oscar-baiting film with the added draw of hot sex. Yet the film sticks with you; predictable and inevitable it may be, but Lee’s hothouse romanticism, and the final haunting image of an empty bed, are hard to shake. Perhaps it’s due to the pull of stories like these, the thrill of illicit activity and the tragedy of lovers that are fated to part. Lee knows that films are a dream machine, and he uses his dream machines as hypnotics, easing us into an absorbed mood as gently as slipping into a steambath. It adds up to movies like this one — easy to admire, difficult to love.