|

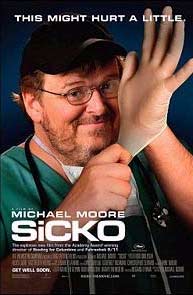

Sicko (2007, Dir. Michael Moore)

“You’re not slipping through the cracks. They made the crack and are sweeping you toward it.”

Yes, believe it or not, Michael Moore is a sensitive soul. You wouldn’t know it from the likes of Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 911, in which the Michigan filmmaker perfected the art of the in-your-face, look-at-me documentary, barely pausing for breath as he linked war, pestilence, and the erosion of everything good about the U.S.A. to the government, corporations, gun manufacturers, oil companies, and just about every other nightmare on the paranoid liberal hit list. Strident and snarky, his documentaries refuse to be ignored, but they also opened themselves up for easy dissection by the ultra-conservatives, who took glee in poking holes in his facts and his sanctimonious crusader persona. When Moore took the mike at the Oscars and bellowed against a “fictitious war” created by a “fictitious president,” one could have seen the disaster coming from a mile away — he was in danger of becoming a parody of himself.

And yet, for all his bluster and self-righteousness, Moore is perceptive enough to know when enough is enough — how else to explain Sicko, his expose on the American health system, in which the rotund, baseball-capped filmmaker refuses to even show himself on screen for the first 40 minutes? When he finally does reveal himself, it is a kinder, gentler Moore that we see, quietly bemused by the follies of health care, sorrowful for an America that is yet to be (“Shouldn’t we be better than this?”). Sure he isn’t above a little showmanship — like when he announces that he “anonymously” paid for the health costs of his harshest Internet critic — but for those who have had enough of his Barnum act, Sicko shows a Michael Moore who is more willing to let the message take the spotlight — and the result is his most devastating film yet.

|

And the message is clear: the United States is screwed when it comes to health care. Beginning coyly with a few horror stories (a man without health insurance gets two of his fingers chopped off in a sawing accident, and learns at the hospital that he only has enough money to reattach one), Moore quickly adds that “this film is not about them”; it is about the millions who do have health insurance, and still can’t get aid when they need it. The litany of wrongdoing is exhaustive and exhausting, and Moore captures a chunky cross-section of it — everything from a taped Richard Nixon conversation in which the president opens the Pandora’s box of privatized health care to pharmaceutical companies who use their influence in Washington to gain hefty contracts, claims adjusters who are under orders to deny care whenever possible, and elderly patients literally getting dumped on the street in front of a homeless shelter because the hospital refused to take responsibility for them. In the end, it all boils down to money: the insurance company, like any good corporation, wants to make it, and patients will be forced to pay through the nose when they spend it.

It’s sobering stuff, and Moore knows it — he lets the interviewees tell their own stories, which are devastating without need of embellishment. A husband dies because a health insurance company doesn’t approve of an experimental drug that might save him. A baby girl dies because the hospital isn’t covered in the mother’s insurance plan. A woman is charged for an ambulance ride to the emergency room because the ride wasn’t “pre-approved” (never mind that she was unconscious at the time). Most affecting of all are the stories of volunteer workers who pitched in at the World Trade Center in the wake of 9/11, and have been refused proper health care for their ailments because they were not “official” rescue workers.

|

Moore also knows when to get slightly whimsical — in response to these tales of woe, Moore pays visits to Canada, England, and France, all of which have successful universal health care programs. This leads to some incredulous, amusing scenes in which Moore, playing up the “it can’t possibly be better than it is in America” shtick, picks the minds of doctors, patients, and expats alike. And he is shocked, shocked to discover that a doctor in Britain can actually own a comfortable home and two cars despite being shackled by an oppressive socialist medical system, or that every citizen in France is entitled to a nanny when a child is born, free of charge, or that American expats in Paris feel a bit guilty about all the quality care they receive as a matter of course while their families back in the States toil all their lives for inadequate coverage.

During the course of his investigations, Moore lobs a few sobering statistics at us, but the point of Sicko isn’t the numbers (no doubt they’ve already been sliced and diced by the critics), but the unease that we all feel about being helpless at the whims of the U.S. health system. Less a documentarian than a rabblerouser, Moore’s movie succeeds admirably as incendiary entertainment, especially when he pulls the stunt of taking the New York rescue workers on an unauthorized trip to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, appealing to the military to let the beleaguered workers make use of the much-touted medical facilities (“We don’t want any treatment better than what the evildoers are getting!”). And even this has a startling payoff, as Moore leads the rescue workers into Cuba proper, where they purchase medicine at a fraction of the cost they would be charged in America, and receive much-needed care at a Cuban hospital. It’s a moment rich in irony — the Cubans, the supposed enemies of democracy and freedom, still provide more humane care to Americans than the Americans would get at home — and even though Moore harps on it a bit too bluntly, as far as rabblerousing goes, it’s a doozy.

|

“Whatever happened to all that lovely hippie shit?” Pete Townshend once wrote in a song, and Sicko closes with a sequence that should warm the cockles of idealists everywhere — the New York rescue workers, having been treated and feeling good for the first time in years, pay a visit to a local Cuban fire department, where they are greeted like heroes. (Sure it was probably all staged and preplanned, but you’d have to be a mighty Scrooge not to be affected by the moment.) As the men and women embrace, national boundaries broken down, compassion and goodwill toward fellow humans carrying the day, Moore dares to suggest that the America he believes in is an America that is capable of such benevolence and generosity, where one is willing to sacrifice for one’s neighbor, with such a sentiment informing our health care, our government policies, our daily lives. For all his calculation and showmanship, it’s somewhat endearing to realize that Moore honestly seems to believe in this stuff, and that for all its statistics and tales of woe, Sicko is really all about how people should be nice to each other.