|

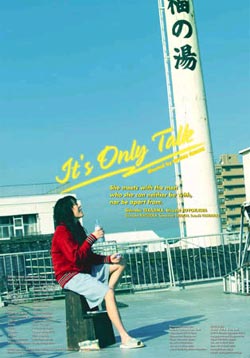

It’s Only Talk (2005, Dir. Ryuichi Hiroki)

“There is no trace of chic in Kamata.”

One of my favorite films from the 2005 SF International Film Festival was Vibrator (2003) by Ryuichi Hiroki. His only previous claim to fame was as a director of “pink” movies, and the scenario of Vibrator has a whiff of that genre (lonely woman spends a few days on the road with a hot young truck driver, indulging in plenty of sex), but the film turned that genre (and the genre of the road movie) inside out: the young woman wasn’t a vacuous sex object but a psychically damaged, flesh-and-blood creature, fully aware that her antics were merely a brief respite from her troubled life. Unhurried and humane, Vibrator can be seen as the descendant of the films of Mikio Naruse, in which women are front, center, unadorned, empathetic, luminous.

Lo and behold, it’s 2007, and Hiroki’s It’s Only Talk is one of my favorite films from this year’s festival. A gentler film than Vibrator, it nevertheless continues down the same road, and it’s an even stronger effort. Hiroki’s movies aren’t plot-driven — a lot happens, and people change, but he’s not one for the standard A-to-B curve of a drama. He prefers to follow the rhythms of his female protagonists — in this case, Yuko (Shinobu Terashima, who also starred in Vibrator), a woman very much on the fringe of Japanese society. In her mid-thirties, struggling with manic depression, unable to hold a job or anything resembling stability, she decides to move to Kamata, a dull little town outside Tokyo, a place where there is “no trace of chic.” Like town, like resident — while both appear to be flat, underneath their placid exteriors is oodles of quirkiness. Soon Yuko is building a website extolling the town’s virtues: a playground made completely of tires (including a towering tire Godzilla), a house bursting with moss on its walls, a ferris wheel that leads to a surprising panoramic view. She whiles away her days with similarly offbeat men: Honmu, an old college classmate who’s now a local politician with problems “getting it up”; Noboru, a manic-depressive yakuza member who longs for the days of his youth; Mr. K, a kindly old man who pleasures her with a vibrator in public places.

|

At first Yuko seems perfectly self-possessed, content to hang out with her odd buddies and shrug off their advances, but then the order of things is upset when her flashy country cousin Shoichi (Etsushi Toyokawa) reenters the picture. An old high school flame (she lost her virginity to him), he’s a bit gauche in his Hawaiian shirts and vintage convertible, and for the past six years, he’s languished within a loveless marriage. We soon learn that in those six years, Yuko was hospitalized for her illness, and has never quite recovered. She’s still given to embellishing on the truth of her background; she claims her boyfriend died in the Tokyo gas attacks, that her parents died in an earthquake. When Shoichi walks out on his wife and crashes at Yuko’s place, the stage is set for some bonding and soul-searching.

Aha, you think; these two will heal each other, and this will lead to a sweet, moving conclusion — maybe they’ll even get together. Well, yes and no. Hiroki isn’t interested in the easy way out — he prefers the journey to the destination. As Yuko and Shoichi grow closer (there are some outstanding vignettes here, including a funny episode at a horse track and a karaoke scene that trumps a similar moment in Lost in Translation), the movie is lighter than air … and then it crashes down when Yuko is hit with a particularly nasty bout of depression. Steadfast and honorable, Shoichi stays with her and slowly nurses her back to sanity, and it is these small scenes (the cooking of dinner, the buying of medicine, the washing of clothes) in which the soul of It’s Only Talk resides. As the title suggests, Yuko’s natterings are a front, a clever means to hide the confusion within, and it is only in silence — the breaking of morning sun through the blinds, a smile of thanks — that true communication lies. When a rehabilitated Yuko and Shoichi acquire two goldfish and name them Laurel and Hardy, it’s a reflection of the film’s theme: a mismatched duo who somehow complete each other. It all builds to a memorable kiss, and an ending that can only be called bittersweet, as each character receives an unexpected but fitting sendoff.

Hiroki is a simple filmmaker: there are no fancy camera tricks or editing on display, just a light touch and an attentiveness to details and his actors. Terashima and Toyokawa have great chemistry, but the film really belongs to Terashima. A well-known stage actor, she seems to have created her own character type in Japanese film: the knowing yet damaged outsider. She’s pretty but not cute; grounded but not stilted; expressive but naturalistic. One moment she seems as young as a teenager, and the next as mature as a middle-aged woman, and her elasticity is perfect for a role like this, in which Yuko is trapped in a neverland between adulthood and adolescence.

The final shot in the movie is Yuko in isolation, sitting in her favorite public bathhouse — in previous visits she had refused to remove her towel because she claimed she was covered in tattoos (another fib, we suspect), but now is she naked, submerged in water, only her face and shoulders visible, tears working their way down her face. “Everyone has gone away,” she sighs. Are her tears those of resignation or catharsis? We’re not sure, and I don’t think Hiroki is, either. Both a return to innocence and an acknowledgment that things always change, It’s Only Talk drips with humanity — a paean to the random connections we make with ourselves and others, a wry confession that life is always in progress.