|

The Painted Veil (2006, Dir. John Curran)

Lift not the painted veil which those who live

Call Life: though unreal shapes be pictured there,

And it but mimic all we would believe

With colours idly spread,–behind, lurk Fear

And Hope, twin Destinies; who ever weave

Their shadows, o’er the chasm, sightless and drear.

Although they are resolutely non-cinematic, something about M. Somerset Maugham’s books has gained a foothold in film — everyone from Greta Garbo to Bill Murray has taken a crack at translating his brittle novels to the big screen. Perhaps they appeal because there is next to no surface in his writings: it’s all about the emotions and spiritual yearnings concealed underneath, which leaves filmmakers free to embellish the proceedings with their own visual polish.

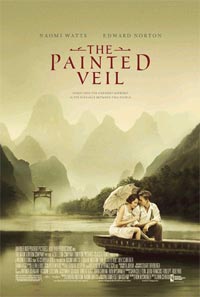

Certainly visual polish is the first thing that springs to mind when it comes to this version of A Painted Veil (the first was made with Garbo back in 1934) — one look at the poster for the film, and it’s clear that this is meant to be sumptuous. (Indeed, the film’s cinematography by Stuart Dryburgh has an unfussy glow to it.) But getting past those surfaces, how does the story fare? When the original novel was published in 1925, the idea of a naive, self-interested Englishwoman discovering herself through helping the benighted cholera-afflicted natives of a backwater Chinese province might have seemed romantic, after a fashion. Today, it seems so imperialistic. How do the novel’s sentiments translate to our current milieu?

|

The answer: Quite well, with a bit of rejiggering. The bones of the plot remain the same: Walter Fane (Ed Norton), an earnest and unexciting young doctor, takes on bored, aging high-society girl Kitty (Naomi Watts) as his wife, and when the two relocate to Shanghai, Kitty’s wandering eye comes to rest on handsome expatriate Charlie Townshend (Liev Schreiber, struggling valiantly with an English accent). When Walter discovers her infidelity, he decides to punish her (and himself) by blackmailing her into accompanying him on a risky assignment to the remote village of Mei-tan-fu, treating cholera victims. The spoiled, frustrated Kitty (her name is no accident) is anything but pleased at this turn of events, but as the couple settle in at the village and she begins to aid in the relief efforts, a gradual but inevitable movement towards responsibility and grace begins.

|

A few changes have been made to the novel’s thrust to enable it to play to today’s audiences. Ultimately, the novel was a father-daughter story, as Kitty must prove herself worthy of her father, and vice versa — a curious thread, since her father is absent for the most of the proceedings. The film shifts the emphasis and ups the romance quotient with Ed Norton; while Walter in the novel is more of a plot prop than a character, Norton’s Walter is given the space to breathe. He may be pigheaded and cold, but he also has the capacity for understanding and even passion, and his altruistic energy helps mitigate some of the “civilized folks condescending to help the natives” vibe of the novel. Also on hand to balance the cultural books is the great Anthony Wong as the local colonel who must politically navigate the villagers’ suspicions, local warlords, and the British aid workers.

|

So we have a more politically correct, more overtly romantic version of an austere Maugham tale — and somehow it works, and the reason it works is Naomi Watts. In the hands of a less accomplished actress, Kitty’s inevitable march to redemption would have come off like a point-A-to-point-B progression. But Watts surprises us by surprising herself: refusing to give in to grand moments of realization and tearful epiphanies, her performance is a slow, telling accretion of details, from petulant silences to little bits of jeering fun at her husband’s expense, to a willingness to open up and experience the world, loathing giving way to understanding and then helping. Her Kitty is a woman running out of options, and her dawning realization of this fact paradoxically opens up the world to her. In the end, it’s less about Kitty and Walter mending their marriage as it is about Kitty finding something within herself, and when Watts meets Schreiber again at the end of the film, the moment has a crystalline clarity to it — we realize how far Kitty has come, and Watts communicates the bloom of that moment (significantly taking place in a flower shop) perfectly. She also enjoys good chemistry with her co-stars Toby Jones (sympathetic and charming as a dissolute English resident of Mei-tan-fu) and Dame Diana Rigg (understated but compelling as the mother superior of the local French mission). Director John Curran avoids pomposity at nearly every turn — always the key trick when it comes to “prestige” films like this — and he also benefits from a memorable score by Alexandre Desplat (with an assist by Chinese pianist Lang Lang).

The film isn’t perfect; although it moves confidently for most of its running time, the climax seems rushed, unprepared for, which dilutes some of the impact of the final scene. Still, The Painted Veil stands as a worthy addition to the Maugham film canon, and it navigates the minefields of being an “intimate epic” quite well. It helps when you have someone like Watts to give the concept of grace the spark of life.